12 Old-School Alcoholic Drinks You Won't See At Parties Anymore

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

For the past several decades, the alcoholic beverages that hosts offer their party guests, or stock their bar carts and drink fridges with, have remained pretty much the same. Beer, wine, and a few standard spirits and common liqueurs still dominate the American alcohol canon. Only the specific brands and styles change, with big breweries, distilleries, and beverage companies routinely rolling out new stuff that they hope can gain not only a big customer space, but a permanent place on the shelf or cart of those who regularly imbibe booze or throw parties where the adult beverages are consumed in mass quantities.

Sometimes those new production introductions take hold and are accepted into party and drinking culture. Novelty is exciting, and so is drinking with friends, and some beverages wind up capturing a moment in time or culture. But then they become so synonymous with a certain period that they can become as passé as quickly as they were the hottest thing behind the bar. That, and people just tend to get tired of beverages if they drink too many of them in a finite period of time.

Here then are some bottled and canned drinks — beers, wines, malt beverages, and hard alcohols — that dazzled fans initially only to fade into obscurity, oblivion, and discontinuation. These are the alcoholic drinks you won't be offered at a party anytime soon.

Purple Passion

The hardest of hard alcohols, the grain alcohol Everclear has an ABV level of 95% (standard vodka comes in at 40%), which is so high that it carries a flammability warning. In some locations, its purchase requires a permit. Marketed as an ingredient for homemade bitters and infusions, Everclear is among the strongest drinkable alcohols. It once made moves into the mainstream, casual drinker market with Purple Passion, a bottled mixed beverage.

As early as the 1950s, college students had been mixing up their own "Purple Passion punch," made by mixing Everclear with fruit and wine, softening the booze and providing a purple hue. In 1986, Everclear launched its own mass-manufactured take, also called Purple Passion. The David Sherman Corporation rapidly sold a million cases of the stuff, sold ready-to-consume in cans, and made with real Everclear spirit.

While it was often remixed over the years, the last widely available version boasted 13% alcohol. In 2014, David Sherman Corporation successor Luxco released a limited-time only Purple Passion revival, but it's since disappeared.

Bacardi 151

One of the highest-proof spirits widely available in the United States for more than 50 years, Bacardi 151 was a specially formulated rum offered by well-known Bermudan rum distiller Bacardi Limited. With a proof of 151 (over 75% ABV), it was nearly twice as strong as Bacardi's flagship rum, which registers an alcohol content of no more than 40% and is good for everything from tikis and Old Fashioneds to Cubra Libre cocktails.

Bacardi 151 could certainly be considered party fuel, metaphorically and literally, as it was usually the alcohol of choice for professional and party bartenders making flaming shots and fiery cocktails, or staging alcohol-related stunts — it was just that highly flammable. Bacardi 151 bottles bore a message advising against such behavior, absolving its producer of culpability if those drinks or tricks went awry.

Still, Bacardi Limited faced multiple lawsuits by consumers who suffered burns from fires ignited by Bacardi 151 rum. After those cases entered the legal system, Bacardi discontinued its demonstrably dangerous high-alcohol rum variant in 2016.

Malt Duck

When deciding what to drink, revelers are often left to choose between a beer or a glass of wine. For about three decades, Malt Duck insisted that party-goers and imbibers didn't have to pick one or the other, because they could have what was essentially both. First distributed by the National Brewing Company in the 1960s and from G. Heileman Brewing from 1975 onward, Cold Duck came in tall, glass bottles and it combined beer (which had alcohol in it) with Concord grape juice (which didn't). When drinkers drank Malt Duck, they'd first get hit with a sweet grape sensation, which then faded out to give way to a distinctive beer aftertaste.

A little sugary and a little boozy made for a popular party beverage to offer alongside the full-on beer and actual wine. Sales had fallen so low by 1992, however, that G. Heileman took it out of circulation and even let the trademark on Malt Duck go unprotected. Wisconsin's Sprecher Brewery secured the rights and in 2016 brought a reformulated, higher alcohol (5.9% ABV) back to stores, but that was only supposed to be for a limited time.

Four Loko

Energy drinks are probably bad for the heart, but that was only one of the problems with Four Loko. It's still sold in convenience, liquor, and grocery stores across the United States, but it's in a version deemed safer than the formulation that debuted with much controversy. Originally called Four in 2005 because it included four powerful mood-altering chemical stimulants — caffeine, wormwood, taurine, and guarana — the malt beverage sold only moderately until the makers dropped the wormwood and doubled the size and alcohol content. The 23 ½ ounce, 12% ABC drinks became a hit on college campuses, where administrations banned the drink after numerous incidents of student hospitalizations over alcohol poisoning. The states of New York and Kansas both banned Four Loko outright.

Manufacturer Phusion Projects marketed and advertised a standard, 23 ½ ounce can of Four Loco to have the same amount of alcohol as one or two regular beers. However, in 2011 the Federal Trade Commission accused Phusion Projects of deceptive advertising. The alcohol content of one can was more akin to that of five or five beers, and would fall under the definition of a binge drinking session. Because Four Loko was sold in aluminum, non-resealable cans, the FTC charged Phusion with encouraging dangerous overconsumption of alcohol, made all the more problematic by the inclusion of stimulants. The Four Loko sold after 2011 is caffeine-free.

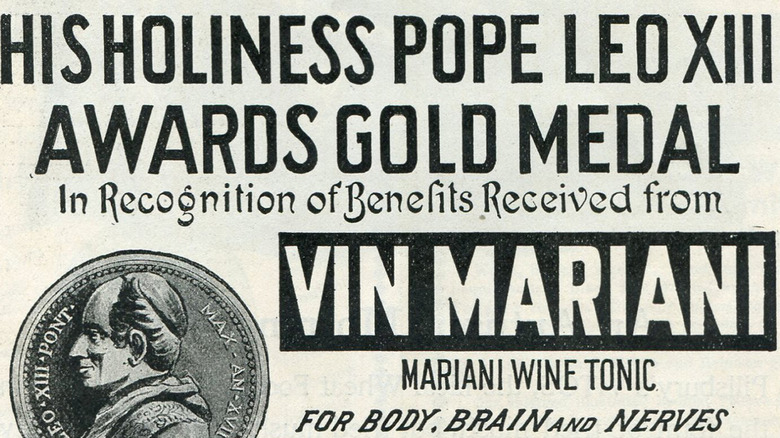

Vin Mariani

After reading an 1859 study about the energy-providing benefits of the South American coca leaf, French chemist Angelo Mariani infused the stuff into Bordeaux wine. That was Vin Mariani, which its creator said could be used as a pep-provider, after-dinner drink, and medicinal concoction. All it really was: strong red wine with 6 milligrams per ounce of what was literally cocaine.

Cocaine is a famously addictive stimulant, and Vin Mariani quickly became one of the best-selling wines in Paris before finding popularity in continental Europe and the United States. Prominent and respected celebrities loved it, too: President Ulysses S. Grant, Queen Victoria of England, writer Jules Verne, and even Pope Leo XIII publicly praised Vin Mariani. Those unprompted endorsements certainly helped fuel sales of Vin Mariani — the drink that got people drunk, high on cocaine, and intoxicated by a third substance, the psychoactive cocaethylene, formed in the liver when it had to simultaneously process alcohol and cocaine.

The Vin Mariani party came to an end in 1906. By that time, the negative health and social effects of cocaine were more understood, and the Pure Food and Drug Act required manufacturers to list certain ingredients on labels and bottles, such as cocaine. Vin Mariani was sold for a while without the drug, but it couldn't compete with the non-alcoholic and also formerly cocaine-containing, but still energizing, Coca-Cola. In 1914, Angelo Mariani died, cocaine was outlawed in the U.S., and Vin Mariani went away.

Zima

The strangest and biggest consumer products fad of 1993: clear stuff. Hoping that Americans could equate transparency with cleanliness and straightforwardness, manufacturers introduced (and then quickly shelved) clear deodorant, dishwashing soap, soda (notably Crystal Pepsi), and alcoholic beverages. Developed by Coors, Zima looked like Sprite, sort of tasted like a Sprite with a little bit of vodka in it, and purportedly had a more pronounced mouthfeel and slightly more calories than a light beer. With Zima, Coors began to attract more women to the beer and malt beverage market.

But Zima was also initially a hit across demographic designations, selling over a million barrels' worth in 1994. The popularity slightly outlasted that of the other clear products — sales cratered by two-thirds by 1996. Zima, consigned to a fate as a flash-in-the-pan and the subject of countless hacky stand-up comedy jokes in its own time and just as many online lists of nostalgic '90s things after, the product didn't die. It sold in small numbers until Coors retired the product in 2008, bringing it back briefly in 2017 and 2018.

Bud Dry

The dry beer craze started in Japan in the 1980s, when brewers of popular brands like Asahi Dry played around with yeast levels, adding so much extra that the living, tiny organisms consumed more of the naturally-occurring starches and sugars than they would in American-style lagers. This produced a beer with just a hint of sweetness, no aftertaste, and a dryness comparable to that of wines which also had less calories (on account of the yeast-consumed sugar) and slightly more alcohol than the competition's. That seemed like a recipe for a very social beverage option, and in 1989 Anheuser-Busch took notice, bringing a spinoff of its flagship Budweiser beer to the American market called Bud Dry. With a nutritional profile similar to Bud Light, it had the higher alcohol content of a standard Bud, and then all of that dry beer flavor profile.

Bud Dry sold well for a few years in part due to a saturation-level advertising campaign that implored consumers to give the odd new product a taste via the catchy rhyming slogan "Why ask why? Try Bud Dry." Very few Bud Dry drinkers became regular Bud Dry drinkers, however, and Anheuser-Busch slowed down production in 2006 before ending it entirely in 2010 — one of the many once-popular beers that have disappeared.

Aftershock

Primarily known for its titular line of bourbon, Jim Beam distills other alcoholic drinks, too, and in 1997 it quietly rolled out Aftershock. With an ABV of 30%, it almost reached the strength of a pure distilled spirit, but it had the look and taste of a liqueur, meaning it was heavily sweetened and full of flavor. It was also brightly colored — a vibrant red to match its aggressive cinnamon taste. Somewhat spicy as a result, Aftershock was a syrupy drink with a lot of presence and, according to the bottle, it delivered a bizarre tandem sensation of heat and coldness.

As if the first Aftershock didn't look and taste like cinnamon mouthwash, Jim Beam added some companion boozes to the line, including a cooling-only citrus flavor that was so blue that it also reminded drinkers of mouthwash, and Thermal Bite, a blue-green mixture that promised extra heat. None have been produced since 2009.

Ripple

Embraced by young adults because it was so different from what their parents drank, and because it was sweet, smooth, and bubbly, and on the whole very inexpensive, Ripple emerged in the 1960s as the wine of choice among hippies and countercultural types. Introduced by gigantic wine conglomerate E. & J. Gallo in 1960, Ripple was something like bottled sangria — low-quality red wine imbued with fruit juice, sugar, and various flavoring and coloring agents — which was then carbonated to add in effervescent bubbles. The signature and original Ripple flavor: Red, shortly thereafter joined on the lower shelves of the liquor aisle by Pear and Pagan Pink varieties.

Gallo's method of marketing Ripple to the youth of the mid-20th century — with ads touting it as a "drink for lively people" (per Facebook) — worked. Musicians helped cultivate the image of Ripple as a cool product, with the Grateful Dead, Motorhead, and Eazy-E all featuring or mentioning it in their works. On "Sanford and Son," one of the most popular sitcoms of the 1970s, Fred Sanford (comic Redd Foxx) often discussed Ripple and created numerous Ripple-based cocktails.

At one point, Ripple could be purchased in gas station vending machines, but not after 1984. That's when Gallo decided to delete from its line anything less-than-classy, introducing recloseable wine bottles and actual vintages while also eliminating bargain-basement offerings like Ripple.

California Coolers

One of Bartles and Jaymes' toughest competitors in the wine cooler segment was California Cooler, a line of sweetened, fruit-flavored, wine-derived drinks sold in multi-unit packs and in large jugs. It was considered a party drink in the 1980s because it was marketed as such – ads depicted young people having fun on the beaches of California, setting forth the notion that California Coolers were simply the bottled, modern version of boozy punches crafted from scratch by surfers on the beach in the 1960s.

It was actually developed by central California-based entrepreneur Michael Crete, who in the late 1970s decided to package his party and barbecue drink of choice: white wine mixed up with fruit juice. Credited as the inventor of the wine cooler, Crete sold the product in beer bottles in order to appeal to younger buyers who he felt would be put off by the pretentiousness of wine that permeated California at the time.

Within four years, more than a million cases of California Cooler, in various flavors like orange and lime, were selling every month. At the peak of the wine cooler fad in 1985, Crete and partners sold the enterprise to liquor company Brown-Forman Corp., and just in time. By 1987, the demand for wine coolers had flattened, and actual California wines had replaced them as the cool party beverage. Brown-Forman started to bottle them less, and by the early 1990s was no longer actively producing California Cooler.

Hop'n Gator

That fun and memorable name refers to the two constituent ingredients: the Hop refers to hops, the bitter flavoring agent used to make beer, and the Gator is short for Gatorade, the revitalizing sports drink invented by Dr. James Robert Cade for use by athletes at the University of Florida in 1965. Just four years later, Cade and his team concocted a spinoff beverage, Hop'n Gator, mixing dehydrating alcoholic beer with the rehydrating Gatorade. That made for a beer made and distributed by Pittsburgh Brewing Company that made for a unique party hit in that the sports drink part somewhat canceled out the deleterious effects of the alcohol part.

Cans billed Hop'n Gator as both a lemon-lime lager and a new alcoholic beverage, and a strong one at that, with 25% more alcohol per serving than the average beers of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Pittsburgh Brewing nor Gatorade could convince many beer drinkers to switch their allegiance to the fruity and watered-down but also more alcoholic beer. The brewery ended production on the beverage in 1975, making Hop'n Gator a discontinued Gatorade flavor we probably won't get back.

Baileys Glide

Irish cream, particularly that made by product originator and industry leader Baileys, has been a party favorite since 1974. Often given away as gifts, the creamy, sugary, low-alcohol liquid dessert is enjoyed on its own, as an additive to coffee, or as one of the best types of liquor to use in a spiked hot chocolate and other sipping cocktails. Baileys and its unique taste are so well known that in the early 2000, manufacturer Diageo tried to make it easier for fans to consume. In 2003, the company unveiled its first ever brand extension with Baileys Glide, a bottled form of Baileys Irish Cream with the alcohol reduced, vanilla added, and sold in 7 ounce, or 200 milliliter, bottles.

With a 4% ABC level, one Glide serving contained only a fraction of the alcohol as its predecessor. Intended to recapture some of the 40% of the Irish cream market that Baileys didn't own, Glide was positioned as a party drink alongside "alcopops" like boozy bottled and canned lemonades. It didn't work, and so Diageo stopped bottling Glide in 2005.