How The Food Pyramid Has Evolved From 1916 To 2026

What and how much should we be eating to maintain good health? It depends on who you ask. There are countless philosophies, programs, and diets willing to answer that question, and every five years, the federal government chimes in with its opinion through the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). The DGA is published jointly by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to promote healthy eating habits, provide nutrition education, and prevent chronic diseases.

The guidelines, used by public and private nutrition programs, were most recently updated in January 2026 with some surprising changes that literally turn long-standing nutrition advice on its head. Scientific understanding of nutrition has evolved massively over the last 100 years and so has our relationship and access to food. We looked back into the history of government-published dietary recommendations and found that while a lot has changed, some things remain the same.

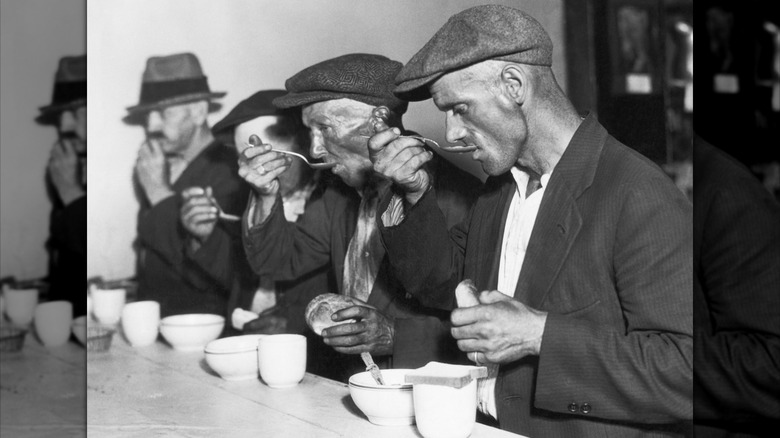

1916 to 1930s: Nutrition for survival

Five food groups — meat and milk, cereals, fruits and vegetables, fats and fatty foods, and sweets — were introduced in the first national food guide, Food for Young Children, in 1916. This became the springboard for dietary guides for people of all ages.

But events like World War I, the Great Depression, and the Dust Bowl limited access to food, forcing people to sacrifice, substitute, and save the food they had. Many Depression-era Meals are still around today. Successful World War I food propaganda influenced America's eating habits, promoting home gardens, food preservation, and creative ingredient replacements.

Growing scientific discoveries of the link between food and health led the USDA to publish a comprehensive food plan in 1933. This identified 12 food groups and their respective nutritional benefits. It included suggested menus at four different price points in order to help people understand how to get the most nutritious meal they could afford.

1940s to 1960s: Nutrition for health

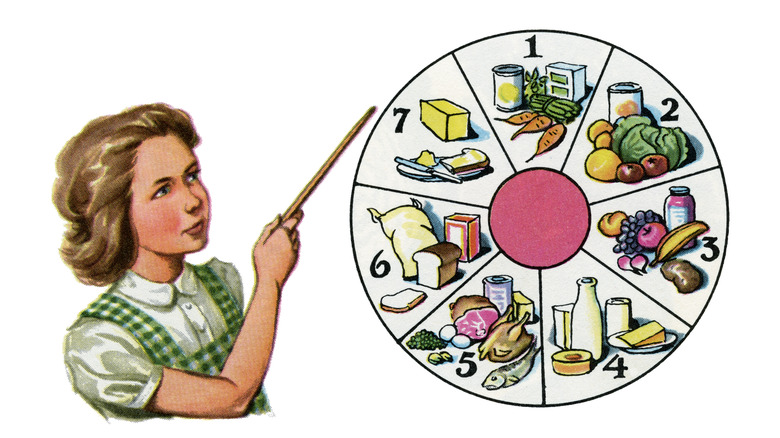

The 1941 National Nutrition Conference for Defense had two important outcomes. Not only did it determine the need for public nutritional education, but it also introduced the first daily Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) to prescribe the necessary intake for nine essential nutrients. From 1943 to 1955, Americans followed the USDA's Basic Seven, A Guide to Healthy Eating, with daily recommended intake of two or more servings each of milk, vegetables, fruits, cereal and bread, butter (yep, butter was its own food group), and one or more servings of meat, cheese, fish, poultry (with occasional beans, peas, or peanuts,) and eggs (or at least three to five per week).

During World War II, the National Wartime Nutrition Guide proposed a diet high in nutrients as a basic eating plan to keep Americans strong. They were encouraged to plant Victory Gardens to grow and preserve their own produce, leaving commercially grown food for the soldiers. Milk was promoted as a healthy choice to replace other ingredients going to support the war effort, though some historians believe the push was due to surplus dairy production more than nutritional value.

Wartime ingenuity introduced new foods into American culture, and while no one is still eating Emergency Steak made from breakfast cereal, many of the food products we eat today were invented or popularized during wartime. By the mid-1950s, the USDA's nutrition guidance had evolved into the Basic Four, which doubled the previous daily recommended intake of meat and grains.

1970s to 1980s: Nutrition for disease prevention

Nutrition guidance changed direction after the 1977 Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs identified that eating too much saturated fat, cholesterol, sugar, and sodium was linked to heart disease, strokes, cancer, and obesity. The committee's Dietary Goals for Americans shifted from recommending minimums of nutritional intake from each food group to prescribing limits on certain nutrients such as cholesterol, sugar, salt, and fat.

In 1980, Americans were encouraged to eat a variety of foods, increase fiber and carbohydrates to 55% to 60% of their daily calories, to maintain an ideal weight, and to avoid too much sodium, sugar, alcohol, fats, saturated fats, and cholesterol, which could increase the risk of some chronic diseases. However, some nutrition scientists, food industry representatives, and members of the public disagreed with the research on which the recommendations were based. In response, Congress called for the USDA and what's now known as HHS to create the first official Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) with the aid of a committee of independent scientific experts.

The subsequent 1985 dietary guidelines were based on three years of research, which resulted in the recommended servings for five food groups – milk, yogurt, and cheese; meat, poultry, fish, eggs, beans, and nuts; vegetables; fruit; and bread, cereal, rice, and pasta. A new sixth group — fats, oils, and sweets — identified foods that should be eaten sparingly.

1990s: The food pyramid emphasizes choices

In the 1990s, the DGA adopted a more encouraging approach, using positive wording instead of negative. Recommending that people avoid foods high in fat became advice to instead choose foods low in fat. Eating certain foods in moderation was encouraged instead of restricting them, and Americans were told they could enjoy food and still make healthy choices.

The OG food pyramid, introduced in 1992, was the first graphic that used the size and placement of each food group to clearly demonstrate the makeup of a balanced meal. The bread, cereal, rice, and pasta group was at the bottom, as the foundation and the largest group, with a suggested six to 11 servings a day. The next level showed vegetables (three to five daily servings) as a slightly larger group than fruit (two to four servings). Above that came milk, yogurt, and cheese, combined with meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs, and nuts, both two to three servings each. The tiny tip at the top of the pyramid represented fats, oils, and sweets, which were recommended to be consumed sparingly. Yellow and white dots within each group gave consumers a general idea of the amounts of fat and sugar typically found in foods in that group.

Looking back at the ready-to-eat meals people were eating in the '90s, it's no wonder that standardized nutritional labels were introduced in 1994 to help consumers apply the principles of the food pyramid to their food choices. By the end of the decade, physical activity to maintain or improve weight had been added to the guidelines as an essential part of a healthy lifestyle.

Early 2000s: Simplifying nutrition for healthy habits

In the 2000 DGA, Americans were encouraged to get back to the basics with a mnemonic reminder to aim for fitness, build a healthy base, and choose sensibly, which reframed but didn't change the basic nutrition principles of the Food Pyramid. The guidance reiterated eating less saturated fats and cholesterol. Vegetable oils were suggested as an alternative to fats such as butter, lard, and margarines and shortenings containing partially hydrogenated oils.

The Food Pyramid got an update in 2005 with MyPyramid, which changed the graphic to colored wedges representing the food groups and included a figure climbing its side to emphasize a balance of nutrients, calorie intake, and physical activity. New changes also included direct instruction on how much people should be eating. A "serving" was too vague, so it was changed to specific, familiar measurements like ounces and cups. And finally, trans fats, an unhealthy fat used in ultra-processed foods, were highlighted as a fat to avoid.

The report said Americans were eating more than enough meat and reiterated the role of fruits and vegetables in reducing the risk for chronic diseases, whole grains in reducing the risk of heart disease, and milk products in reducing the risk of low bone mass, but clarified that the dietary health benefits were more likely when part of an overall healthy diet rather than related to one specific food group.

2011-2025: MyPlate provides examples and alternatives

The dietary guidelines got a new, simplified look in 2011 with MyPlate, a graphic of a table setting with the dinner plate and cup with colored wedges of varying sizes representing the five food groups. A quick glance at the graphic suggested that, at each meal, half the plate should be filled with fruits and vegetables, the other half split between grains, protein, and a smaller portion of dairy. New guidelines encouraged swapping solid and saturated fats with healthier fats, which played a role in the renewed popularity of avocado toast.

In 2020, the Make Every Bite Count campaign encouraged people to choose nutrient-dense foods and beverages, with a focus on overall healthy eating patterns. It promoted whole fruits, whole grains, fat-free and low-fat dairy or dairy alternatives, lean and low-fat meats, seafood high in healthy fatty acids, and eating vegetables and protein from a variety of sources. Online tools allowed customization of meal plans based on age, lifestyle, culture, budget, and personal taste.

The 2020 guidelines included recommendations for infants and toddlers for the first time in 35 years, a helpful tool for parents battling picky eaters. Recommendations for sugar intake were to choose foods and beverages with little or no added sugars for those ages 2 and younger, and for no more than 10% of daily calories to come from sugar for children and adults. Moderate alcoholic drink consumption was defined as a maximum of one per day for women and two for men.

2026: The New Pyramid calls for significant changes to the American diet

The 2026 dietary guidelines call for big changes to the Standard American Diet, which it says often consists of processed foods and sedentary lifestyles. It is the first DGA to specifically address highly processed foods and their effects on overall health, weight, and the risk of disease. The main takeaway messages are to eat more wholesome foods, cut out highly processed foods, and severely limit added sugars.

The New Food Pyramid flips some long-standing guidelines on their head — literally — by using an inverted pyramid graphic. The top and widest area shows intake of protein, dairy, and healthy fats on equal footing to vegetables and fruits, and places whole grains in the smallest area at the bottom — a total reversal to the original pyramid, which was based on grains. Consequently, the new recommendations increased protein intake and reversed recommendations for dairy from low-fat or fat-free to whole-fat.

These are the first DGA to mention the importance of gut health, citing how highly processed foods are disruptive to a healthy microbiome. Guidance on alcoholic beverages was simplified to consume less. The sweeping changes align with the Make America Healthy Again campaign from the United States secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and are an attempt to shift Americans away from the dietary patterns he believes have contributed to increased rates of chronic disease.

New pyramid: Reverses recommendations for protein and dairy fats

One of the biggest changes recommended in the new pyramid is prioritizing protein at every meal, with a suggested daily intake of 1.2 to 1.6 grams of

protein per kilogram of body weight. Another surprising change is the move back to full-fat dairy products. Low-fat and fat-free dairy products have been the standard for the past 40 years.

Saturated fats have long been recognized as unhealthy, and now their main sources — meat and full-fat dairy — are placed prominently on the new pyramid, but the cap on saturated fats remains unchanged at no more than 10% of daily calories, which seems contradictory to some, as there is no mention of the role of lean meats.

In the new guidelines, healthy fats are defined as those from whole foods, such as meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, nuts and seeds, olives, avocados, and dairy. Vegetable oil, an unsaturated fat that has been promoted as a healthy alternative to saturated fat in the past, is not mentioned, but olive oil, butter, and beef tallow (which is increasingly used to cook French fries at restaurants) are suggested sources of healthy fats.

New pyramid: War on sugar and highly processed foods

Sugary treats, dining out, and pre-packaged convenience foods — all of which are integral parts of America's food culture — are on Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s hit list, with sugar as his primary enemy. Artificial colors, flavors, preservatives, and sweeteners are included in the new guidelines as ingredients to limit, in addition to low-calorie, non-nutritive sweeteners, with a particular emphasis on avoiding sugar-sweetened drinks.

The negative impact of excessive sugar intake on health has been known for more than 60 years, tied to America's obesity epidemic and increased rates of diabetes and disease. While recommendations to limit sugar intake are nothing new, they get an extreme makeover in the 2026 guidelines. The new recommendations are a dramatic reduction from 12 teaspoons of added sugar per day to about 10 grams or less per meal. And that's just for adults. A revolutionary shift in sugar recommendations for children aged 10 and under is that they should not eat any added sugars. None. That one's particularly hard to swallow for those who know how much kids crave sweets.

Added sugars are in pretty much all processed foods, which makes things like bottled marinara sauce and energy bars more unhealthy than we realize. Adherence to the recommendations will require discipline to opt for homemade, nutrient-dense whole foods rather than highly processed convenience foods and dining out.

New pyramid: A bold response to a health emergency

The number of overweight or obese and diabetic or prediabetic adults was nearly the same in the 2020 and 2026 Dietary Guidelines reports. In 2020, 74% of adults in the U.S. were overweight or obese, while 46% had diabetes or prediabetes. In 2026, more than 70% of adults were overweight or obese, and 50% were diabetic or prediabetic.

While the 2020 report noted that chronic diseases were common in Americans, the 2026 Dietary Guidelines For Americans uses more provocative wording, such as "health emergency," "crisis," and "devastating" to reinforce the urgency of the need to address poor eating habits to improve overall health, and calls for a focus on prevention, instead of intervention.

The 2020 report claimed that the increase in the number of Americans experiencing diet-related consequences was due to the fact that, for decades, the majority of people have not followed the advice outlined in the guidelines. However, the 2026 report blames poor research, past policies, and the influence of pharmaceutical companies for contributing to the health crisis.

Reactions to the new nutrition guidelines

Every new edition of the Dietary Guidelines comes under scrutiny, with stakeholders flagging conflicts of interest, industry influence, and confusing or contradictory advice. In 2026, members of the advisory committee expressed concern that their report was rejected and replaced with one that was written by a new panel, many of whom had ties to the beef and dairy industry. In contrast, some nutritionists and health experts welcomed the dietary changes, confident they were not influenced by prominent businesses in the food industry.

Reactions were mixed among food industry representatives. The limits on sugary beverages, added sugars, and sugar substitutes sparked a nerve with the American Beverage Association, which said they were "impractical and inherently contradictory" (via Reuters). SNAC International took offense to the advice to avoid prepackaged snacks because they are highly processed. Meanwhile, the American Heart Association supported the limits on sugary and processed foods but expressed concern that promoting full-fat dairy and red meat could result in diets high in sodium and saturated fat, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

The International Dairy Foods Association praised the prominence of full-fat dairy in the new guidelines but expressed concern that the term "highly processed foods" — which did not come with a clear definition — could be applied to milk, yogurt, and cheese, which are processed for quality and safety reasons. The Center for Science in the Public Interest also claimed that promoting butter and beef tallow as healthy fats was "contradictory" and "blatant misinformation."

The new guidelines will impact school lunches and federal food assistance programs

Federal food programs must comply with current dietary guidelines, so changes are coming to food assistance programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and school lunches. The biggest change is that there will be an option for whole milk in the lunch line for the first time since 2012. Milk has been mandatory for all federal school lunch programs since 1946. Initially, it was exclusively whole milk, but low-fat options appeared in the '70s. It wasn't until the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 that whole milk disappeared, as well as flavored milks. However, flavored milks returned when milk consumption subsequently took a nosedive.

Changes to school lunch menus take a few years to roll out, giving food manufacturers and cafeteria workers time to adapt. The 2023 adjustments to school lunches aren't yet totally in effect, and it isn't unusual for them to be altered based on feedback. The Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act made major changes, requiring significant cuts in sodium and saturated fat, the use of whole grains, and increased servings of fruits and vegetables — even encouraging schools to install a salad bar. In 2018, due to pushback over product availability, cost, and food waste, the USDA softened some of the requirements for sodium decreases and whole grains.