12 Foods With Shady Origin Stories

The whole world of food, and all of the individual culinary cultures that contribute, is a testament to the strength of the human mind and the power of ingenuity. Everybody needs food to survive, and countless tasty foods were born out of urgent need. For the entirety of history, people have made do and derived sustenance from what they have or have access to. That has often included naturally growing produce and spices, parts of animals previously deemed unusable or unwanted, and other stuff that people thought might not even be edible. Necessity is the mother of invention, as goes the phrase. It's a very modern phenomenon to eat with taste or artfulness in mind, or to allow the creative impulse to drive the development of foods.

But the desire to eat and drink, as well as the desire to make a profit, can also pull the dark side of humanity into the game. A shocking number of commonly available and even mundane and taken-for-granted foods emerged from strange, uncomfortable, and awful circumstances, involving war, slavery, drugs, racism, corporate espionage, blatant theft, and even the unspeakable. Here are 12 familiar foods with beginnings that are either twisted or uncomfortable to hear.

M&Ms are a candy clone

In both the U.S. and the U.K., a certain type of mass-produced chocolate candy is ubiquitous, and it has been for generations. Sold first to the military for WWII soldier ration packs, Mars Inc.'s M&Ms have been a favorite since the 1940s — round morsels of firm chocolate encased in thin candy shells in a variety of colors. But in the U.K., such candies are known by a different name: Smarties. English company H.I. Rowntree & Co. became a major candy company in the U.K. after first gaining a toehold in 1882 with Smarties, a packaged version of comfits, a candy once made from sugar-coated nuts and seeds. Thrown at brides on their wedding day in Europe's Middle Ages, by the 1800s, chocolate had replaced the nuts and seeds.

While Smarties were part of a legacy, M&Ms directly and expressly cribbed from Smarties. In 1937, Mars founder Forrest Mars visited Spain and noticed Spanish Civil War soldiers eating rationed Smarties, a unique chocolate product in candy shells that prevented melting in the hot sun. Mars returned to the U.S. and oversaw the development of a very similar candy, M&Ms, named after himself and business partner Bruce Murrie (which is the reason each candy is stamped with a little 'M.')

Nabisco took everything from Hydrox to make Oreos

Nabisco markets its Oreo cookies, even when the science goes too far, as "America's favorite cookie," which is at least partially true. The simple construction of two chocolate discs held together by a thin dollop of sweet and chalky creme filling has sold well since their 1912 debut in a single store in Hoboken, New Jersey. Not only have dozens of Oreo flavors and styles been introduced in the century-plus since, but other cookie manufacturers have released their own take on the idea, usually with a twist. Newman-O's are made with more natural ingredients than Oreos, while Hydrox cookies look and taste almost exactly like the sector-dominant cookie. Seen as an Oreo clone or slightly cheaper undercutter, Hydrox actually predates Nabisco's flagship treat by many years. Its slogan, "America's Original", is a subtle yet true assertion that the creation of Oreo was an act of industrial thievery.

In 1908, Sunshine Biscuits sent out the first batches of Hydrox, a chocolate sandwich cookie whose scientific-sounding name is a combo of "hydrogen" and "oxygen," or the component elements of water. It was supposed to suggest a cookie that was pure, clean, and wholesome. Instead, it may have reminded consumers of chemicals — the Hydrox Chemical Company even sued Sunshine Biscuits for infringement. Nabisco saw a good idea and improved on it, giving it a more marketable name and removing the slight bitterness from the Hydrox original recipe.

Pop-Tarts popped up to outpace the competition

Since 1964, Pop-Tarts have been a grab-and-go breakfast for millions. The thin, sometimes frosted and sometimes not-frosted pastries stuffed with some kind of sweet paste or fruit jam were a logical line extension for Kellogg's, best known for popularizing the idea of eating a bowl of cereal for breakfast. But the food company got a big assist from the competition when it came to devising its wildly successful product. Before Kellogg's ever sold Pop-Tarts in sealed metallic pouches, the idea actually came from cereal world competitor Post.

In the late 1950s, Post had a pet food division that created Gaines Burgers, a meaty dog food that stayed wet without refrigeration. The technology that made it possible was developed elsewhere in Post, and one group used it on fruit, which led to the idea of a non-spoiling jam inside of a very thin pastry shell rendered as a four-sided treat. That became Country Squares, and Post talked them up at various food industry events. Pundits predicted massive sales for Post and Country Squares, but a lead time of about six months between announcement and retail rollout gave Kellogg's plenty of time to rush its own competing product to market. By the time Country Squares arrived, Pop-Tarts had already been selling well, behind a significant advertising campaign, for a while. Country Squares looked like a knockoff, and the product died a quick death, much like many future discontinued Pop-Tarts flavors.

Taco Bell looked across the street for inspiration

The first Taco Bell opened in Downey, California, in 1962. One of the first and most influential Mexican-inspired fast food chains, Taco Bell's original limited menu offered little more than burritos, tacos, and beans, or frijoles. Its signature item: ground beef, cheese, and lettuce placed into a steadfast tortilla that's fried, creating an easy-to-replicate hard-shell taco.

Such cuisine had already enjoyed some regional popularity in California for decades, however. One very popular restaurant in the Los Angeles adjacent town of San Bernardino was the Mitla Café, a Mexican eatery with a big clientele since it opened its doors in 1937. The enterprise of Lucia Rodriguez, an emigrant from the Jalisco region of Mexico, served a mashed potato taco and one with a filling of ground beef, cheese, tomatoes, and lettuce. Both came in a hard-shell taco, which Rodriguez is credited with introducing in the United States. Bell opened a burger and hot dog stand across the street from the Mitla Café in 1948, and after observing the brisk sales of hard-shell tacos, added the beef version to his menu, later developing the Taco Bell menu around it. He learned how to make them from the Mitla Café. "I remember him," Rodriguez's daughter-in-law recalled in Gustavo Arellano's "Taco USA." Bell would "come in late at night, ask lots of questions about how we made tacos, and then leave."

The origin of pink lemonade is a real circus

Pink lemons are real and come from nature; they're a relatively rare fruit identified in 1930. Pink lemonade, on the other hand, is completely artificial. As tasty and refreshing as standard lemonade made with the perfect ratio of water, lemons, and sugar is, pink lemonade has an inviting, pastel, candy-colored appearance. It gets that color from artificial means today, usually a food dye, which, for all their faults, is still a better pink-providing agent than what was used on the original drinks.

The origins of the transparent beverage are murky, but the two most likely stories both involve a traveling circus. In the 1850s, Pete Conklin, brother to a famed lion-tamer, got a job on the circuit selling lemonade to patrons. He reportedly went to make a new batch one day, and near the potable water earmarked for lemonade, he found another tub sitting around. Conklin didn't know that the water wasn't clean, and that a circus performer had used it to rinse her pink tights. Noticing that the lemonade came out pink, Conklin called the stuff "strawberry lemonade," and it caught on as a circus-specific beverage. Another story, set in the same era, holds that Henry Allott, an employee at a different circus, was messing around in the concessions one day and knocked cinnamon candies into some lemonade. It dyed the whole bucket pink.

Pozole used to be primo cannibal cuisine

Of all the soups and stews associated with Mexican cuisine, pozole is perhaps the most famous and most adored. Often eaten on or around Christmas, the slow-cooked stew almost invariably revolves around a pork shoulder, accompanied by hominy and red chiles, and it's finished with the addition of cabbage, radish, avocado pieces, and cilantro. Often thought of as a homemade dish, pozole appears on Mexican restaurant menus, too.

Pozole is an old dish, and it's much older than its country of origin, predating the formation of Mexico and the influence of Spanish colonialism by hundreds of years. Much of what is now Mexico once belonged to the Aztec empire, which frequently engaged in religious festivals that involved ritualistic human sacrifice. To honor certain gods, captured members from other communities, often felled warriors or the enslaved, were killed, skinned, and mutilated. Aztec cooks serving high-ranking officials would then use the leg meat of the vanquished to prepare a celebrational stew made with many of the same ingredients that are still used in pozole today. When Spanish colonists arrived and eradicated the Aztecs, they stopped such cannibalistic rituals from occurring. Pozole evolved, with locals making use of rodent meat before moving on to chicken and pork.

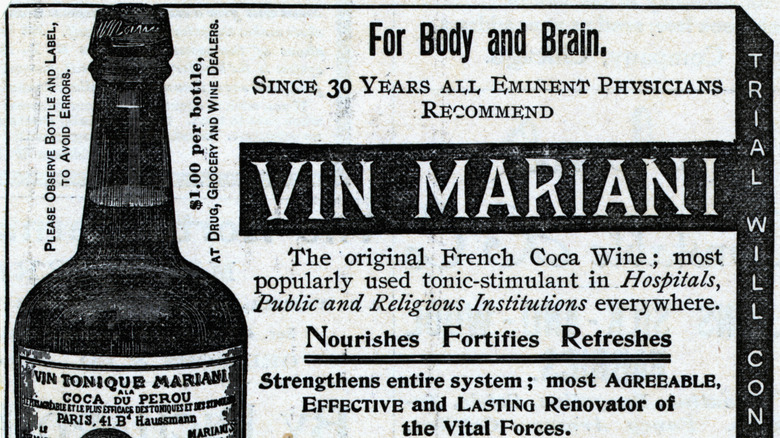

When you can't have cocaine wine, have a Coke instead

One of the best-selling and most heralded bottled beverages of the late 19th century: cocaine wine. After reading about how the South American coca leaf was an effective stimulant, French chemist Angelo Mariani acquired some and infused it into Bordeaux wine. His concoction, Vin Mariani, was marketed as a medical aid, an aperitif, and an invigorating substance — after all, it was strong wine mixed with a generous serving of cocaine. The notably addictive substance fueled tremendous international sales of Vin Mariani, with Queen Victoria and Pope Leo XIII among its most public fans. The success of the product led to many other addictive cocaine wines hitting the market, including one made by John Pemberton of Georgia.

Pemberton suffered such extensive harm during the Civil War that he became addicted to the morphine that was supposed to relieve his extreme pain. Seeking to ease his addiction, Pemberton thought that cocaine would help both himself and others, and in 1885, he bottled and sold Pemberton's French Coca Wine. Just a year later, an alcohol law forced Pemberton to remove the wine from his Coca Wine, and he replaced it with carbonated water and some other flavorings. That was the first iteration of what would become Coca-Cola.

Welsh rarebit's history is more hateful than cheesy

Both a precursor to and slightly fancier of the grilled cheese sandwich, Welsh rarebit consists of toast abundantly slathered in a creamy cheese sauce flavored with tangy mustard. It's one of the few foods internationally associated with Wales, where it's considered a national dish. It may not actually come from the U.K. member nation, and its name may have originated as an insult from the English.

For centuries, dairy farming has been a major practice in Wales, and so cheese has historically been part of the diet. At the same time, Wales was a rural, remote, and economically disadvantaged place, and cheese provided the dietary protein that came from animals in other places like England. When Wales was politically merged into England in 1536, an influx of Welsh emigrants into English cities brought with them various examples of melted cheese cuisine, which was looked down upon and joked about, deemed lower-class or negatively exotic. One such dish the Welsh enjoyed for its inexpensiveness as well as its taste: melted cheese on toast. Britons derisively nicknamed it "Welsh rabbit," suggesting that the Welsh were so poor that when they did eat meat, it was because they'd hunted small game like rabbits. Over the centuries, the name evolved from Welsh rabbit to Welsh rarebit, a conscious softening of that nasty and classist attitude.

7-Up was an antidepressant

While there are only a handful of nationally produced, big-brand lemon-lime sodas on the market today, in the late 1920s, there were more than 600. Into that crowded market emerged Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda in October 1929. This one, concocted by Charles L. Grigg, was more expensive than the vast majority of other, similar soft drinks, but it had a special ingredient: lithium citrate. That's a form of lithium, a naturally occurring salt and chemical element that was one of the first widely-prescribed and effective treatments for clinical depression and bipolar disorder.

Shortly after Bib-Label Lithiated Lemon-Lime Soda debuted, Grigg renamed his product 7-Up Lithiated Lemon Soda, and then just plain 7-Up. The meaning of the name was never revealed by Grigg; the 7 is truly a mystery, while the "Up" likely referred to the drink's slight mood-boosting capabilities thanks to the inclusion of an antidepressant. 7-Up contained lithium until 1948, when a new formula had to be invented after the FDA banned the use of the chemical in the food and beverage supply.

Original Fanta was gross and made for the Nazis

Fanta, one of the most omnipresent orange sodas, hit U.S. stores in 1958. However, that formula was far different from its original permutation. The United States joined World War II in 1941, after it had already been in progress in Europe for two years. American companies were ordered to drop all ties to combatants, which forced Coca-Cola to stop supplying syrup and ingredients to its subsidiary in Nazi Germany, Coca-Cola GmbH, with whom it had kept doing business throughout Adolph Hitler's conquest of Europe in the 1930s. That put Coca-Cola GmbH head Max Keith in a bind. Germany was a major Coke market, and instead of losing customers, letting the business shut down, or allowing it to be seized by the Nazis, he asked company chemists to create a new soft drink, just for Germany.

Severely limited by rationing measures, Keith's scientists gathered the production waste of other German food companies. Stewed together and flavored with alternative sweeteners like beet sugar, Coca-Cola GmbH took fruit peels, apple pulp, and whey — the liquid produced during cheese-making — and made a new drink. The company called it Fanta, an abbreviation of fantasy. As the war progressed, there weren't a lot of other soda options available in Nazi Germany, so sales were good to modest; many households used it to bolster scratch-made meals in the wake of wartime ingredient scarcity and rationing.

Graham crackers are supposed to purge the urge to merge

The National Biscuit Company, later known as Nabisco, debuted Honey Maid graham crackers in 1925, one of the first (and still extant) brand-name versions of that snack. That essentially ended the century-long evolution of the graham cracker, winding up with a standard idea that's the complete opposite of what its inventor envisioned. In the 1820s, minister and current speaker on the touring Pennsylvania Temperance Society, Sylvester Graham, espoused that the emotion of lust was physically harmful, the true cause of most issues, from headaches and indigestion to epilepsy and mental illness. In order to get physically healthy, he argued, one had to quell their sexual urges, and they could do it with his sedate vegetarian diet.

Graham eschewed meat, fat, spice, caffeine, and alcohol, and ate plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole wheat, fiber-rich foods. To that end, in 1829, Graham promoted a recipe for the Graham cracker, made primarily from coarse whole wheat flour and without fat, sugar, or salt. Eating that cracker, Graham claimed, would calm any and all carnal urges. He never patented the recipe, so others could use it and expand upon it. In 1881, the first contemporary graham cracker was suggested by the 1881 cookbook "The Complete Bread, Cake, and Cracker Baker," which added animal fat and molasses to the mix and helped eventually make the food a part of the best S'mores.

Okra came to the South secretly, through the enslaved

Okra is viewed as a distinctly Southern food. It grows throughout the region and is important to the food culture, where it's used in a variety of ways, notably as a fried vegetable side and one of the main flavoring additions in gumbo. Okra seems to thrive in places where it can get quite hot, like the South and western Africa. And that connection is precisely how okra arrived in the Americas.

The vegetable was likely first discovered and definitely cultivated in ancient Egypt, where it was known as kemet. Its use spread south into Africa, where it was a vital crop by the 16th century. That's when the transatlantic slave trade began, and persisted for about 300 years. As slave traders invaded western Africa and violently kidnapped people to place them on boats bound for North and South America, many people smuggled out okra seeds or hid them by braiding them into their hair before they were forced onto the ships. Okra became a reminder of home for those ripped away from it, and it was soon found growing in the places where slaves were the most exploited.