The Controversial History Of McDonald's Founder Ray Kroc

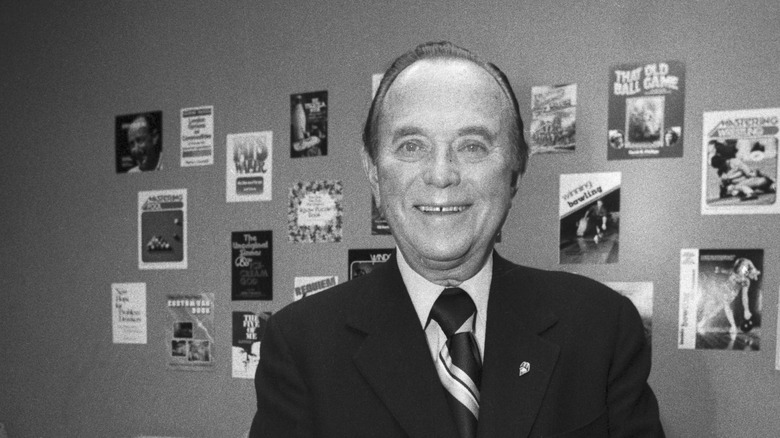

If one knows even a little about the history of fast food or the underlying machinery of American big business and the global spread of capitalism, then they've probably heard the name Ray Kroc. He's credited as being the individual most single-handedly responsible for making McDonald's the fast food standard-bearer, not to mention its role as one of the wealthiest, most popular, and omnipresent restaurants and brands of all time. Nicknamed "the founder" for his vital role in the enterprise, Kroc is hailed as a hero of business and a true innovator who connected people with some of the best-selling food items in McDonald's history.

But the widely known and disseminated story about the rise and domination of Kroc has been fudged and fabricated. The story of McDonald's, as it relates to Kroc, is one of cutthroat and aggressive business deals, and it's largely glossed over by the so-called founder's company ever since he started making overtures in the 1950s. While McDonald's is one fast food restaurant that may never live down its shady past, Kroc's story is a fascinating one nevertheless. Here's the shaky, scandalous, and real story of the professional life of Ray Kroc of McDonald's.

Ray Kroc was a semi-successful cup and milkshake machine salesman

Ray Kroc wasn't a young man when he began his journey to make McDonald's one of the most recognizable restaurants on the planet. He'd already lived a lot of different lives and attempted multiple professions before he stumbled on the early fast food industry. After finishing his sophomore year of high school in Chicago, 15-year-old Kroc dropped out to join the war effort, signing up with the Red Cross Ambulance Corps after fibbing about his age. He only got as far as Connecticut for training, because World War I concluded in 1918 before he could ship out. He returned to Chicago, and rather than go back to school, he found jobs to support himself. By 1922, he was working two jobs: In the day, he sold paper cups for the Lily Tulip Cup Co., and at night he played the piano on live radio broadcasts.

The cup sales job, which he worked at for around 15 years, put Kroc in contact with Earl Prince who was selling the Multimixer: a five-spindle milkshake mixer that he'd invented. Kroc left Lily Tulip and bought the marketing rights from Prince. For 17 years, Kroc traversed the United States, working as a traveling salesman for his own enterprise, hawking and selling multimixer milkshake machines to the increasing number of diners and fast food restaurants popping up around the country.

He latched onto two small business owners in California

Ray Kroc was 52 years old when he discovered the thing that would make him unfathomably wealthy. In 1954, during his era selling Multimixer milkshake machines, he took notice of Dick and Mac McDonald, who had ordered eight of the devices. Intrigued and baffled by how one restaurant might need to make 40 milkshakes at a time, he visited McDonald's, a walk-up service hamburger stand in San Bernardino, California. Kroc was dazzled and inspired by the operation. Like White Castle, the first ever fast food restaurant, the consistently busy McDonald's eatery sold only simple hamburgers and cheeseburgers, and little more than fries, soda, and milkshakes. A truncated menu allowed for more efficient production, which in turn could guarantee really fast service and rock-bottom prices.

Convinced that the concept could be popular anywhere and everywhere, the day after his first visit, Kroc approached the McDonald brothers with a proposition: Open a whole bunch of identical burger stands elsewhere in the United States. At the time, they had already let 10 franchisees open other McDonald's restaurants in Arizona and California. To expand the business outside of California, the McDonald brothers accepted Kroc's offer to serve as their first franchise agent. At the very least, any new restaurants meant some guaranteed Multimixer sales.

Ray Kroc pressured the McDonalds to franchise

At first, Ray Kroc had to be quite persistent when he approached Dick and Mac McDonald about expanding their operation. In fact, the brothers who ran the first McDonald's burger spot in San Bernardino, California, had already explored growing the business. The original McDonald's was a drive-in barbecue opened in 1940. Eight years later, the brothers revamped it into a walk-up serving just burgers, potato chips, soft drinks, and coffee. (They would later add french fries and milkshakes.) It was so popular that in less than six years, they sold the McDonald's concept to be re-created by 14 franchisees, 10 of which actually wound up opening a restaurant.

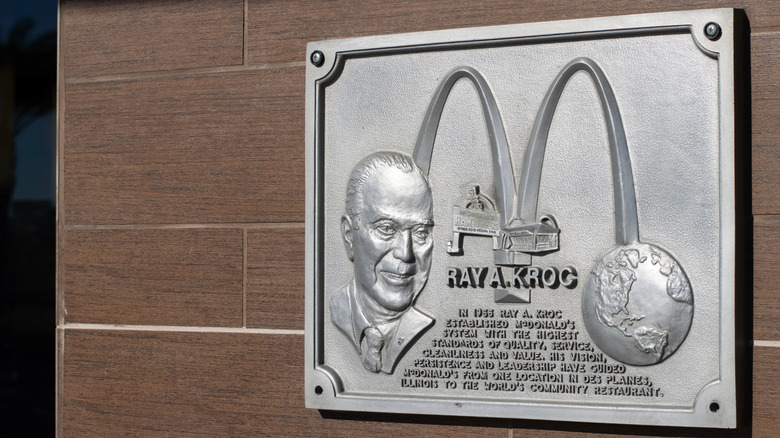

The McDonalds were hardly business savvy and didn't have much interest in growing the company themselves anymore, so they allowed Kroc to take charge of that aspect. Less than a year after pleading with the McDonalds to let him franchise their restaurant, Kroc opened the first non-West Coast McDonald's in Des Plaines, Illinois, in April 1955. McDonald's, the company, even considers Kroc's first store to be the first overall McDonald's, and the McDonald's #1 Store Museum operates on that site today, although that's not quite historically accurate.

He figured out a shady way to make money off of every McDonald's

By 1956, Ray Kroc had opened several McDonald's as a franchisee. While business was good, the burger joints weren't as profitable as he'd hoped. At the very least, not enough money was coming in to propel Kroc's idea of taking the revenue generated by a few McDonald's to fund the construction of more stores. His restaurants didn't generate nearly enough money — he operated on a 1.4% profit margin on 15-cent burgers. Plus, it costs a lot to open a fast food franchise: Operators have to pay insurance, taxes, and a large portion of their revenues back to the head office. So, Kroc brought in business consultant Harry Sonneborn, who had a solution: He advised Kroc to think of his McDonald's enterprise in real estate terms. They founded Franchise Realty Corporation, which oversaw land acquisition and restaurant construction.

Here's how it worked (and how many McDonald's still operate today): The company leased land and built a store there. A franchisee would then sublease the land and building, charged 20% more than what Kroc and Sonneborn had to pay. Before long, that figure jumped to 40%. Franchisees also paid rent on their restaurants and were responsible for a negotiated monthly payment or 5% of gross sales, whichever was bigger. All of these profits, along with security deposits and other fees paid by franchisees, allowed McDonald's to open hundreds and then thousands more restaurants in the coming decades.

Kroc bought McDonald's out from under its creators

Remarkably successful in just a short time, by 1960, Kroc had put together a string of 228 franchised McDonald's that were pulling in $56 million annually (adjusted for inflation, that's nearly $600 million). However, Kroc personally saw relatively little of that. He was entitled to a 1.9% cut from franchisees, more than a quarter of which he had to push over to Dick and Mac McDonald. Hardly content with this arrangement, Kroc called the McDonalds in 1961 and asked what it would take for him to buy the rights to all things McDonald's. Their quote: $2.7 million.

Kroc didn't have that kind of money to spend, and he refused to relinquish control of his franchising company by giving shares to banks in exchange for loans. Eventually, he found a solution: He could borrow it against a few college endowment funds with a 6% interest rate plus ½% of all McDonald's profits going forward. "The $2.7 million ended up costing me $14 million," Kroc told Time in 1973. "But I guess there was no way out. I needed the McDonald name and those golden arches. What are you going to do with a name like Kroc?" Kroc bought McDonald's in 1961 and acquired his nickname "the founder" — not because he founded McDonald's, but because he developed it and turned it corporate.

Kroc killed the McDonald brothers subsequent endeavors

With $2.7 million, Kroc closed the deal with the McDonald brothers to buy the company. The sale included everything –– the name, the golden arches logo, and the right to build and run as many restaurants as he wanted, whether through the McDonald's Corporation or franchising system. But before they signed off on the agreement, the McDonalds had one final request: They didn't want to give up their original restaurant, and persuaded Kroc to let them keep that first McDonald's in San Bernardino.

Kroc would get the last laugh, however, after a savvy but petty business move. Because Kroc owned the trademark, the brothers (aka the actual founders) could no longer use the McDonald's name or insignia. They had to change the name to Mac's Place, and then the Big M. Those phases were short-lived because Kroc ordered the construction of a brand-new, company-controlled McDonald's on the same block. "I ran 'em out of business," Kroc accurately explained to Time.

The founder introduced steadfast principles to McDonald's

Ray Kroc didn't pull the entire McDonald's concept, nor the repeatable procedures that result in a well-liked and uniform product, out of his own imagination. He wanted to get involved in the business because he saw right away how lucrative such an efficient and reliable restaurant could be. Using heat lamps to keep food warm was an idea pioneered by the McDonald brothers, for example. That said, Kroc's main role in making McDonald's a juggernaut was solidifying and finalizing the approach to fast food and customer service for which the brothers had laid the groundwork.

Kroc broke down McDonald's guiding principles into an abbreviation employees are expected to commit to memory and follow: QSC, short for "quality, service, cleanliness." The executive was especially concerned with the "C," which also included a subtle but very real aversion to loitering. "We made sure that no McDonald's became a hangout. We didn't allow cigarette machines, newspaper racks, not even a pay telephone," Kroc told Time. "We made the hamburger joint a dignified, clean place with a wholesome atmosphere."

Kroc was adversarial and competitive with franchisees

It wasn't until 1965, more than a decade into his entrenchment at McDonald's, that Ray Kroc would allow anything beyond burgers and fries onto the burgeoning chain's national menu. And even then, getting a new sandwich launched didn't come without significant resistance and a battle with a franchisee fueled by pettiness and pride. Lou Groen operated a McDonald's franchise in an area of Cincinnati with a large number of Catholic residents. During the 40-day pre-Easter period of Lent, Catholics practice self-sacrifice and austerity, which includes not eating meat on Fridays. Groen observed that his restaurant's revenues fell catastrophically every Lenten Friday, so he proposed a way to attract Catholic clientele: a sandwich made with a deep-fried whitefish patty, approved for consumption.

Kroc was dismissive of Groen's sandwich, which would later become McDonald's iconic Filet-O-Fish. He thought restaurant staff would find it too tough to make, and he pushed for stores to adopt another meat-free sandwich instead: The Hula Burger. All it was: a slice of grilled pineapple and a slice of processed cheese slapped on a bun. Kroc was so convinced that his idea surpassed Groen's that he set up a one-day test market at select locations, promising to nationally roll out whichever meatless sandwich sold the most. The Filet-O-Fish finally got approval after it outsold Kroc's pineapple sandwich by a count of 350 to six.

The McDonaldland characters were copied from a popular TV show

In the midst of McDonald's explosive growth and untouchable popularity in the late 1960s and early 1970s under the full control of Ray Kroc, the fast-food giant sought to expand its marketing reach. Burger-loving clown character Ronald McDonald had been used since 1963 to increase McDonald's awareness among children. In 1970, Kroc's company set out to build upon the character and create a recurring advertising motif: the world of McDonaldland. The company's advertising agency, Needham, Harper & Steers, approached Marty Krofft, one of the Krofft brothers, responsible for the era's many surreal and monstrous live-action Saturday morning shows like "Sigmund and the Sea Monsters" and "H.R. Pufnstuf." While some early development meetings took place, McDonald's agency then decided to abandon the campaign.

At least, that's what it told the Kroffts. In 1971, the first McDonaldland ads hit the small screen. Produced with a crew that included some former Krofft employees, several elements in the initial McDonaldland ads looked suspiciously like Krofft creations, unpaid for and uncredited. In their lawsuit filed against McDonald's and its ad agency, the Kraffts alleged that McDonaldland resembled Living Island from "H.R. Pufnstuf." They also asserted that Mayor McCheese closely mirrored their show's title character. The TV people won the case and were eventually awarded over $1 million in damages from McDonald's. Mayor McCheese was phased out, and McDonaldland and its denizens were redesigned.

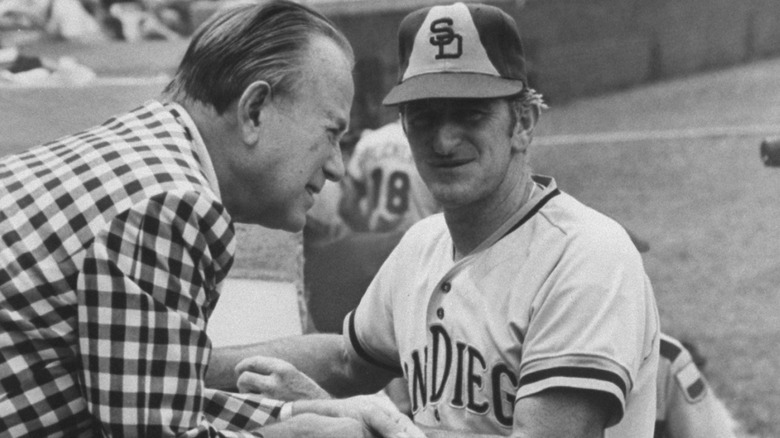

The McDonald's leader was a terrible baseball team owner

By 1974, Kroc had amassed a personal fortune in the area of $500 million after transforming McDonald's into a multi-billion-dollar company. It was a mere pittance then when he dropped $12 million on the San Diego Padres. At the time, the Major League Baseball franchise was the most moribund team around. An expansion team that began play in 1969, it had never finished above last place in the National League West. When C. Arnholt Smith put the Padres up for sale in 1973, one group planned to move the team to Washington, D.C., until Kroc abruptly bought the team. "Because I needed a hobby" was the reason he told reporters at the time (via UPI). Coincidentally, he'd also just been rebuffed in his bid to purchase his favorite (and hometown) team, the Chicago Cubs.

Almost instantly, Kroc grew frustrated with the Padres' continued poor performance. Public meltdowns in front of players and employees became common. During the Padres' very first home game in 1974, Kroc commandeered the PA during a Padres loss and called out, "Fans, I suffer with you. I've never seen such stupid ballplaying in my life," (via the San Diego Union Tribune). Kroc then poured millions into the team, purchasing the rights to star players past their prime who couldn't turn things around. In 1979, the MLB front office fined Kroc $10,000 for violating negotiating rules in trying to lure Reds star Joe Morgan.

The Happy Meal and Big Mac were not new ideas

McDonald's is forever linked with the fast food kids' meal. Along with small portions of a burger, fries, and a soft drink, the brightly-colored Happy Meal box included a free toy. Within the company, McDonald's touts regional ad campaign manager Dick Brams as the "father of the Happy Meal," but all Brams did was come up with the branding. The Happy Meal debuted in 1979, by which time Kroc had moved into the position of senior chairman of the board of the McDonald's Corporation. Six years earlier, the biggest competitor to McDonald's at the time, Burger Chef, had unveiled its Fun Meal, the actual first fast food kids' meal — burger, fries, cookie, and drink — that included a small toy and came in a dazzling box. It was one of Burger Chef's most popular items, and the chain filed suit after McDonald's pilfered the idea.

Another famous McDonald's item was similarly invented by someone else and added to the menu under Kroc's watch. Within the sketchy company culture Kroc cultivated, this item was released as if it were a new idea. The Big Mac, which narrowly avoided a different, ridiculous name, was introduced at a Pennsylvania McDonald's run by franchisee Jim Delligatti in 1967. With its construction of three bun pieces, two patties, and special sauce, the Big Mac was an obvious re-creation of the Double Decker Burger, sold by the once omnipresent Big Boy chain since the 1930s.