What Really Is American Food?

What is American food? What is America? Go ahead, we're all waiting. It's not like it's a difficult question or anything. Had Europeans never made it over here, maybe the answer would be simpler: American food would be what the native peoples of this land fostered and ate. However, Europeans did come, throwing the whole notion into chaos and, in the process, creating an at-times baffling, more often than not derivative, yet completely unique and mightily influential food culture.

Although there are always nuances throughout their different regions, many other countries simply have a stronger gastronomic identity than the U.S. When someone mentions Greek food, or French food, or Indian food, you can picture a certain thing. Certain ingredients, certain flavor profiles, and a particular aesthetic are often perceived to be time-honored and indelible to that place and people. But it's slightly more complicated in the United States.

The same culture that brought the world Little Caesar's also delivered some of the world's most spectacular fine-dining restaurants. The same culture that sells sprayable whipped cheese also has the most cosmopolitan food cities. It's a culture whose culinary heritage has been heavily influenced by other cuisines, yet the ingredients and flavorings originally cultivated in this soil have also irrevocably transformed cuisines everywhere. This is American food. But what actually is it?

Many ingredients we still use today are indigenous to this land

Most of us complain about travel, but let's take a moment to appreciate the first humans to arrive in the Americas. When those hardy, intrepid people journeyed here tens of thousands of years ago, they were confronted with mammoths, giant bears, saber-toothed cats, and sloths the size of RVs. The enormous beasts were happy either eating them or stomping them into prehistoric jelly. Not fun.

The upside is that those same humans were also introduced to the super-region's bounty of native plants, fruits, vegetables, and spices that are still in our diets today. These ingredients were growing wild throughout the lands, with squash being one of the first foods to become domesticated once agriculture was initiated on this side of the world. As humans settled further into the continent, they came across and eventually cultivated the likes of peanuts, chili peppers, tomatoes, and cocoa (chocolate). These four alone have gone on to become staple components of food cultures the world over, not only in the U.S. What are Reese's Pieces without peanut butter? Our salsas and Buffalo wings without peppers? No tomatoes? You can forget about pizza. And chocolate? Is it even America without chocolate?

Aside from these and other iconic fare, spices derived from indigenous vegetation have long animated our palates: allspice, sumac, mint, sage, and juniper, to name just a few. Those early Americans probably had no idea the nutriments they were gathering and farming would, across many centuries and ages and societal evolutions, help shape the likes of Del Taco. Oh, and our entire modern landscape of eating.

Ancient Native Americans planted the seeds of American cuisine

Cahokia, a Native American city that once thrived near today's St. Louis, had a staggering population of at least 10,000 before the Renaissance even hit Europe. A kind of Mississippian New York City, its existence justifiably reshuffles our Old World-versus-New World outlook regarding civilization. It also begs the question of how it fed its thousands of denizens, who lived both within and around the massive, mound-based metropolis.

Archaeological evidence shows that the highly organized city satiated its masses with corn, squash, grains, seeds, and native game, used in stews, porridges, bread, and hominy. Cahokia was an urban center for the pre-Columbian Mississippian people, but it was really a culmination of Native American genius from across the continent. This agricultural brilliance was apparent in the use of the Three Sisters method after Indigenous farmers discovered that planting the trio of corn, squash, and beans next to each other was both productive and sustainable.

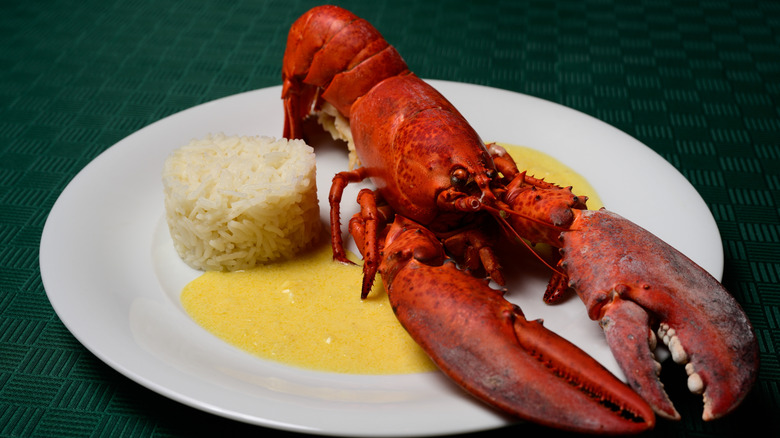

Native American groups developed their own regional meals based on what was available locally. Along the eastern coasts, you had dishes that included fresh fish, shellfish, and clams. In the southeast, you had succotash. The people of the Great Plains feasted on loads of bison, venison, and rabbit, often cooked over an open fire. In the southwest, you had clay pot cooking with ingredients like maize, sunflower seeds, and trout. And up the West Coast into what is now Alaska, people feasted on game, berries, and the biggie: salmon. In each of these native styles of cooking, we see the ancestry of our present-day American food cultures, from New England seafood to Southern soul food to California cuisine.

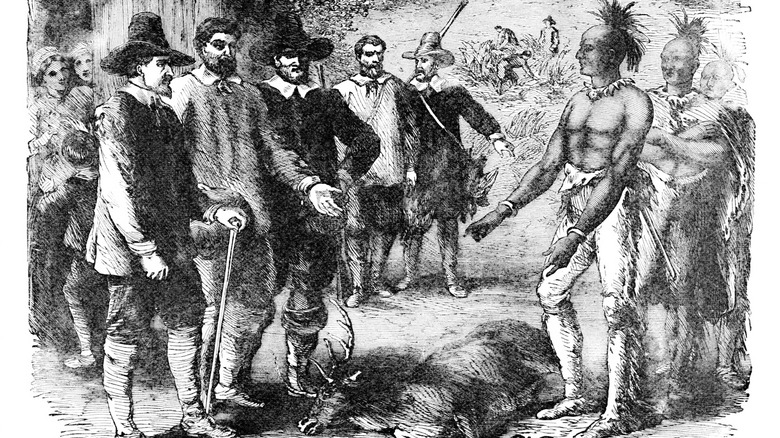

Europeans came and food was never the same

Europeans settled on the American continent in the 15th and 16th centuries. This marked huge changes in how the world eats and what American food would become. For example, settlers brought with them two animals that changed the course of gastronomy on these shores: pigs and cows. Can you fathom this country's food life without either pork or beef? Nathan's would be having a gourd-eating contest every Fourth of July.

The Pilgrims of New England were in dire need of sustenance after arriving in the New World. Having, in short order, run out of the stuff they brought (flour supplies were dwindling, the barley was primarily used for beer, and the peas and other plants proved less than fruitful), the Pilgrims had to rely on Native American help. Tribes like the Wampanoags taught them how to farm, hunt, and fish. Corn was a godsend to these under-resourced newcomers, who were able to use the crop for bread, beer, and other things.

Meanwhile, the Dutch settlement of New Netherland – which included the future site of New York — had a somewhat smoother culinary symbiosis. The Dutch introduced livestock, apples, and wheat to the nearby Indigenous tribes. Native Americans introduced corn and squash. They also taught the Dutch how to make a cornmeal-based porridge called sapaen that the Netherlanders loved and relied upon. The Dutch returned the favor by getting the Native Americans into bread, pretzels, and even cookies.

The Thirteen Colonies loved freedom and beer

By the time the English took control of the Eastern seaboard and the 13 colonies were formed, what and how Americans ate started to look somewhat similar to what we enjoy today. Although the exact cuisines still varied from area to area, colonists would have partaken in something close to cereal for breakfast, meat, bread, and cheese for lunch, and stews, savory pies, or porridges for dinner.

Dessert would be on tap sometimes, too. Sugar was hard to come by, but maple syrup, honey, and molasses could sweeten baked items such as fruit pies. Even fried dough was a common item in certain colonies. So, next time you're at a fair chowing down on a funnel cake for one, you can do so knowing that your ancestors may have done the same.

One thing that can't be overstated is the vast quantity of alcohol consumed by the colonists. They basically had beer or hard cider with most meals. Even the kiddos drank a diluted kind of brewski. It's thought that colonists in the 1700s drank about double the amount of alcohol annually that we do today. George Washington, Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson — they all liked a drink. The boozy intake was for good reason, however. Water at the time often came from polluted sources, so an alcoholic beverage seemed like the safer option. It's amazing to think the Revolutionary War was won by an army nursing a persistent hangover. Imagine a cannon blast after a night out on ye towne? No, thanks.

Increased immigration diversified America's foodie scene

The beginning of the 1800s in the young, freshly independent United States would look like a distant, far-gone world by the end of the century. The country would undergo an epic metamorphosis in those hundred years, in many different ways. Two of those transformative areas would be directly linked: immigration and food.

Chinese immigration began in the 1820s but accelerated during the Gold Rush. It was a similar trajectory for Mexicans after many were initially folded into the U.S. population through territorial gain. Over the course of the 1800s, there was a deluge of immigration from Western Europe – especially Germany, Ireland, and Italy. Things changed accordingly. Street vendors started hawking a wider range of foods, reflecting the cuisine of their home countries, while grocery stores began selling imported food goods.

The result: foods and drinks we now couldn't imagine living without entered the American diet for the first time. Tamales, spaghetti, sausages, pickles, and fried rice are just a few of the other headliners that began filling American bellies during this era. And let's not forget that Germans practically created the modern American beer industry by introducing lager to these shores and starting iconic companies like Anheuser-Busch and Pabst.

Restaurants became more commonplace in the 1800s

In the 1830s, two Italian-Swiss brothers — Giovanni and Pietro Delmonico – decided to change things up at their sweet shop in Manhattan. The entrepreneurs set up tables and invited customers to come in, sit down, and enjoy fresh plates of food. These patrons received a document to see what was available and how much it cost. Thus, America's first fine dining restaurant was born. Sure, taverns and inns and other public houses had been offering eats for ages.

But Delmonico's in New York City, along with Antoine's in New Orleans – the oldest restaurant in the state – were fresh harbingers of things to come. Delmonico's not only pioneered this kind of refined public eating, but also boasted the man considered to be America's first celebrity chef, Charles Ranhofer. The concept of a restaurant, as we know it today, is something we often take for granted, but it has only been around for less than 200 years. Many Europeans in the early days would deride American food after visiting — including Charles Dickens, whose culinary experiences in the U.S. were disastrous.

Although you could say that Dickens's great expectations were not met, it's inconceivable to imagine America without this social innovation. Everything from The French Laundry to IHOP owes its existence to the roots planted by America's oldest restaurants. And sure, menus from this bygone era feature things we probably wouldn't see at our neighborhood Applebee's — namely, pickled lamb's tongue, stewed prunes, scrambled eggs with kidney, and something called Scotch woodcock — they did feature now-familiar American fare like hash browns, gumbo, soft-shell crab, and tons of ice cream.

The Old World created iconic U.S. food

If you were to ask someone to name a quintessential American food, chances are either hamburgers, hot dogs, or pizza will be mentioned. Like Elvis Presley, the Harlem Globetrotters, and Hulk Hogan ripping off his shirt, those three foods just scream America at the world — which is itself a very American way to go about it.

But it was Germans in 19th-century New York who first sold hot dogs from carts and stands. We have Germans to thank for the hamburger, too. It's all in the name, of course. People immigrating out of Deutschland from the massive port of Hamburg took a dish called frikadellen with them, which was basically cooked ground meat. As it traveled throughout the States, it came to be called Hamburg steak and was put in between slices of bread — for the first time, allegedly, at Louis' Lunch in Connecticut (which still exists today).

And then there's pizza. Sure, toppings on flatbread have been around for ages. There's even a depiction of one such concoction on a mural at Pompeii. But the iconic American pizza that we know was brought here by Neapolitans in the late 1800s and early 1900s (although it didn't really gain mainstream popularity in the U.S. until soldiers returning from Italy after World War II developed a craving for it). Topped by the tomatoes Europe would have never known existed if it wasn't for the Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples, one can argue that pizza — along with hamburgers and hot dogs — represents the essence of what American food is: the Old World using the New World to create something novel and accessible.

American food becomes processed

World War II had an irrevocable influence on how Americans eat. An army marches on its stomach, as Napoleon famously said, and U.S soldiers in the trenches of European and Pacific battlefields had to be fed. American industry responded by mass-manufacturing processed food that was ready-made, portable, and storable.

Eventually the war ended. Companies were stuck with a surplus of canned, prepared product. At the same time, the mainstream American housewife – who had been propping the homeland up on her shoulders and kept it running while the boys were off fighting — was returning to life in the kitchen with less taste for domestic duties. Manufacturers solved their glut by parlaying this newfound antipathy. They refined and marketed processed foods to the general public. Advertisers touted everything from condensed soup, Spam, and TV dinners to Minute Rice, Frosted Flakes and Tang, framing them as miracles that would make life easier and freer for everyone in the household. Food was gelatinized, powdered, whizzed, and supposedly good for you (but really wasn't). This changed the American stomach forever — often not for the better. (Couldn't have been a good sign that cigarette companies like Philip Morris jumped into the processed food game, applying their unscrupulous marketing tactics.)

The other side of this mid-century revolution (devolution?) in American satiation was the rise of fast food. This came with construction of the national highway system. People got out and drove, travelling longer distances on commutes and travels. This shrunk the amount of time people spent preparing meals, and made places like White Castle (the forerunner), McDonald's, Dairy Queen, and Kentucky Fried Chicken inextricable facets of American food life.

Is American food today both everything and nothing at all?

Despite Big Macs, Blizzards, and the Colonel becoming the country's taste ambassadors to the world, a look around the contemporary American food landscape offers a more varied view. Informed by its land's millennia of fertile production, the constant influx and inheritance of cultures, traditions, and ideas, and a magnetic presence in the modern world, you see an abundance of cutting-edge gastronomic creativity that is cross-cultural and ever-evolving.

You can also still see the low-brow, ultra-processed, junk food side, which is also cross-cultural and ever-evolving. There are the classics. There are the oddities. There are the innovations. And all the categories are flexible. Today, pizza is still a paragon in the U.S., but avocado toast is probably consumed as much as hot dogs. Expensive meats can be as beloved a post-bar munch as a hamburger. Duck foam stands alongside frozen burritos. And if you ask Americans themselves what genuine America food is, they'll throw out a whole range of eats: Texas barbecue, popcorn, scrapple, key lime pie, pork roll, German chocolate cake (named after an American dude with the last name German, by the way), New York cheesecake, cheesecake ice cream, fajitas. Maybe it's not about asking what American food is, but what it definitely isn't: one, definable thing.