18 Vintage Candies You Won't Find At The Movie Theater Concession Stand Today

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

A night at the movies is almost unheard of without a soda, bag of irresistible movie theater popcorn, and a box of candy in hand. The early movie palaces once considered snacks at the cinema low-brow, but the Great Depression changed everything. In an attempt to lure back patrons, the theaters started to offer concessions at stands in the lobby. Candy and popcorn entered the picture in full by the 1930s, and the sweet and savory deliciousness of going to the movies became the treat of an experience that endures to this day.

While lots of movies are memorable in their own right, for many moviegoers, the experience is fully completed with a box or bag of candy. Joe Baltake wrote in The Philadelphia Daily News back in 1983, "Jujyfruits and Good 'n' Plenty are dependable, the kind of candies you can have a relationship with. They're always there, in every theater, and they're always the same. They give you security."

Back then, it probably would have been unfathomble that either of those candies would no longer commonly be found at a movie theater's concession stand, and yet they've gone. Those two candies are not alone, as many classic ones have now become bygone ones, making space for more modern favorites. Let's turn back the clock and pay tribute to many of those old-timey candies that once made movies truly magic, but now have disappeared.

Bit-O-Honey

Schutter-Johnson Company introduced Bit-O-Honey in 1924. The six-piece candy bar is honey taffy with bits of almonds within, which are both sweet and chewy. It also, rightfully so, came in a bit(e) size as well.

The candy was a long-running movie theater staple. In 1941, The Charlotte Theater in North Carolina enticed kids to be one of the first 300 to show up on Saturday and earn a fee big bag of Bit-O-Honey. Sherry Crawford, a film critic for The Evansville Courier used candies as a rating system, like Milk Duds, Snickers, Good & Plenty, and as a kind of positive one — Bit-O-Honey, which she rated "Home Alone." Bit-O-Honey today is kept buzzing about by the fine folks at Spangler, which also has classic candies like Dum Dums and Necco on its roster.

Boston Baked Beans

Pork and beans with a healthy touch of molasses is a Massachusetts state staple called Boston Baked Beans. Candies using the same name started to be peddled towards the end of the 19th century, and the one that has set the standard to this day was the one that Salvatore Ferrera stirred up at his eponymous Chicago-based company back in 1924. Ferrera's candy had the outward look of beans, but were essentially peanuts enveloped with a reddish-brown candy coating, packaged in boxes wide and small.

In John Douglas Foster's book about fallen Vietnam War soldiers, "Heroes on the Wall," a childhood friend shared the memory that Nicholas Wagnan was an expert at movie candies, but his favorite was always Boston Baked Beans. The candy still hung around at theaters in 21st century but, like Goobers, may have been edged out for good by Peanut M&Ms.

Candy cigarettes

Cigarettes and movies have a long storied history, with actors puffing away on them on the big screen and, for quite a while, paying customers smoking them in the theater. Chocolate versions of cigarettes appeared on the scene around 1915, and by the 1930s, the more common sugar candy sticks not only looked like the genuine article, but the packs themselves looked like real brands. The tobacco companies were on board with this likeness, and studies have shown that this partnership led many of those kids who enjoyed the candies to grow up to become real smokers.

When concerns about smoking started to come to a head in the 1960s, the tobacco companies distanced themselves from the candy versions. In 1976, theaters started to ban smoking inside the venues, and Public Service Announcements screened at trailers from the likes of John Waters to Robocop to reinforce its new taboo nature. Today, the sight of either real or candy cigarettes (which are still legal in America) in a theater would be as out of place as seeing someone on their phone back then.

Chuckles

In 1921, Fred W. Amend Company turned a new jelly candy into a bit of a laugh when it introduced Chuckles. In an early ad in the Decatur Evening Herald, the company founder described them as, "a dandy, old-fashioned, fine, sugar candy — pure as a baby's smile. I call them Chuckles, because they tickle the palate." For comedies, dramas, and all kinds of films in between, Chuckles were a long-time common sight at the movies, and a nice alternative to the usual chocolate options.

Nabisco acquired Chuckles in 1970, and the candy slowly faded in popularity over the next decade. In the mid-'80s, with the rise of gummy candies, Chuckles saw a bit of a resurgence. Today, it resides under the house of so many former concession stand greats – Ferrara Candy Company.

Chunky

There are two theories as to how the Chunky bar got its name — it's either founder Philip Silvershein's nickname for his daughter Roberta, "chunky baby," or because neighborhood kids called Silvershein "Mr. Chunky." Either way, Chunky got its start in the 1930s, and the bar featured Brazil nuts, cashews, and raisins wrapped in chocolate.

The long bar form seen at concession stands eventually gave way to its more common look today — a pyramid-like square in a shiny silver wrapper. Nestlé took over as the makers of Chunky in the 1980s, during its heyday, and ditched the Brazil and cashew nuts in lieu of including cheaper peanuts. Today, Chunky is made by the Ferrero Group, and mainly lives large far outside of movie theaters.

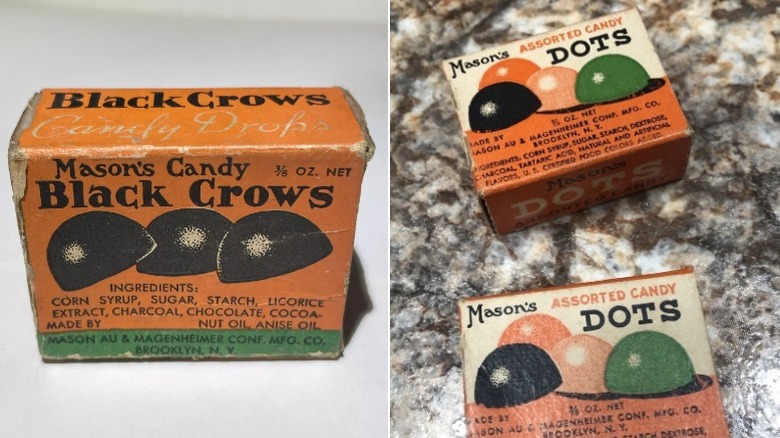

Crows / Dots

Gumdrops were introduced sometime around the 1860s, and were originally a hard candy. Things eventually softened up for the "goody goody" confection, which became a domed, squishy, and chewy gelatin-based treat, often covered in sugar. One variant that was trademarked in 1912 was a black licorice drop by Mason's that long went by the name of Black Crows. The popular movie candy came in a little box, and eventually were joined on stands by an assorted fruity variant called Dots by the 1940s.

Tootsie Rolls Industries acquired Mason's in 1972. By the early '80s, the word "Black" had been dropped from the candy's name, and they slowly disappeared from theaters. Storied newspaper and TV film critic Gene Siskel was a fan of Crows, and during a public discussion on movie concessions at 1986's ShoWest convention, made the case that they needed to return to the concession stand's glass case. If he were around today, he would also probably champion the return of Dots, too.

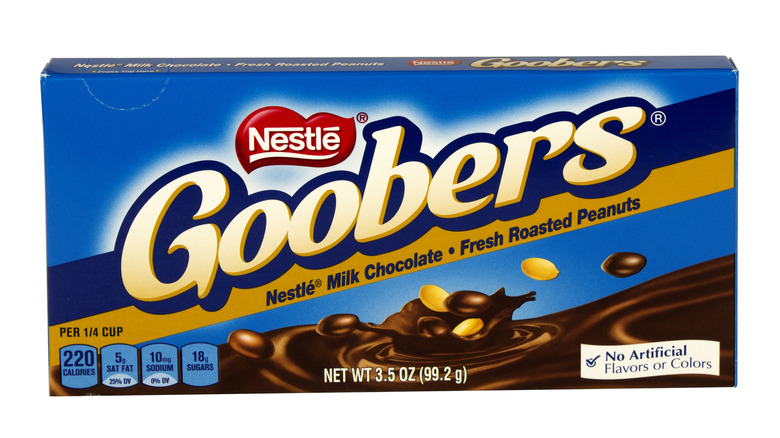

Goobers

Jacob Beresin, who helped introduce the idea of popcorn in theaters, approached the Blumenthal Brothers Chocolate Company about adding some candies to the mix. The end results were Raisinets, Sno-Caps, and Goobers. A "goober" is a nickname for a peanut that dates back to at least 1834, and the candy borrowing that name which launched in 1925 was simply the nut covered in chocolate.

While Raisinets, and to some degree Snow-Caps, had hung around in theaters, Goobers seem to be the odd man out. That still hasn't stopped them from creating permanent movie memories. When renowned interior designer Ellie Cullman was asked by Blue Carreon for her book "Conversations" to describe happiness, she replied "sitting in the dark movie theater with a box of Goobers in one hand, and a box of Raisinets in the other."

Good & Plenty

With a birth year of 1893, Good & Plenty have the distinction of being one of the oldest branded candies in America. The candy coated licorice confection comes in signature purple and white pills.

Good & Plenty was created by the Quaker City Chocolate and Confectionery Company, and had long been an option at movie theater concession stands, and in people's memories. In his book, "You Can Be Whatever You Want To Be," Ted Baxter recalled, "One of my fondest memories was at the age of five years old, when I took my girl friend Lois to our local Ritz Movie Theater to see the movie 'The Wizard Of Oz' in 1939. It cost 10 cents each to get into the movie and 5 cents for a box of Good and Plenty, which Lois and I shared during the movie."

Film critic Roger Ebert was a fan, and was often seen eating them at screenings. The candy joined the Hershey's family in 1996, and today is apparently not good enough for theaters to sell.

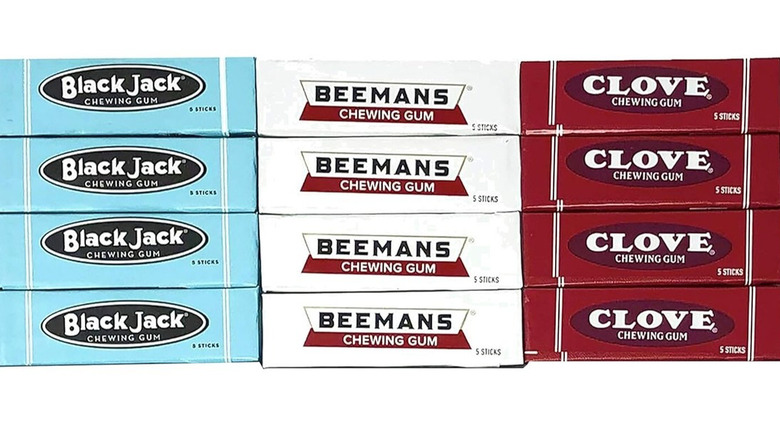

Gum

Gum first entered in the movie theater's picture by way of vending machines in the 1910s, including a nifty contraption that never really caught on called the "midget," which attached to the backs of seats and dispensed pieces. That was followed by stand-alone vending machines in lobbies, and by the 1930s, a place at concession stands. No wonder chewing gum magnate William Wrigley was an investor in the early Chicago chain of Balaban and Katz theaters.

However, gum proved a sticky nightmare for theater owners. In 1925, the Keith-Albee chain tried to "stamp out the gum habit," as reported in Automatic Age, noting the obvious, "It also often happens that the theater has to make good damages that are caused by the careless parking of gum on seats or other places where it might do harm."

Alas, by the 1950s two thirds of theaters were still selling gum, as a headline in the Boxoffice: The Modern Theater told all: "Added Profits from Chewing Gum Sales Outweigh Cleaning Problem Occured." By the mid-1980s, the mess proved to not be worth it, as theaters stopped selling packs.

Jordan Almonds

Jordan Almonds' name first came to light by around 1615, but this candy's origin dates back much longer. The actual almonds used may have hailed from the namesake middle eastern country, and the colorful, thin sugar coating applied in Ancient Rome to form the candy known as "confetti." These candies were used for special occasions like weddings and births.

While many candy makers have made Jordan Almonds, the only most commonly sold in theaters was boxed under the company name Banner since the 1940s, and hung around in theaters until the 1970s. A former concession stand worker confessed on Facebook why they may have disappeared from theaters, saying "when a fresh case was opened and they tasted great — a very fresh almond with a candy shell that broke easily. Once they went bad they were either too hard or the almonds tasted acrid. [It was] The most refunded candy."

Juicelets

Juicelets was a hard candy that first came to market in 1945, and was manufactured by Chicago's F & F Laboratories, a company perhaps best known for its cough drops. Juicelets came in a couple flavors, such as assorted fruit flavors, and Wild Cherry.

Juicelets were sold at movie concession stands through at least the 1950s, as a commentator on Facebook fondly remembered, "We got the most for our nickel if we bought a box of Juicelets. Lasted a lot longer." The candy hung around until at least the late '80s, when the New York Times described its current iteration as "a somewhat bland gummy candy made with purees of oranges, lemons, limes, strawberries and grapes."

Jujubes and Jujyfruits

Heide used to be one of the biggest names in candy, but today the name has disappeared from shelves and even memory. Some of the company's major players still exist, including chewy Jujyfruits, and its harder, smaller, teeth-sticking brother, Jujubes. Jujyfruits are like a softer, more fun version of Dots, with its flavorful candies in the shape of the fruits and veggies. In the early 1950s, the candy was a top 10 seller at movie theaters. In 1975, William Speers reported in The Philadelphia Inquirer that even at an art house cinema, one moviegoer "chases his Jack Daniel's with Jujyfruits."

By the mid-'80s, Jujubes had fallen out of fashion at the movie theaters. The Salisbury Post reported in 1985 that kids didn't always take to the flavor and spat them on the floor, creating a similar clean-up mess that spelled doom for gum's existence in theaters as well. While not as messy, Jujyfruits saw the same fate, and both are now sold by the Ferrara Candy Company.

Necco

The New England Confectionery Company, aka NECCO, traces its roots to 1847. The company was best known for its eponymous wafers. Waxy packages of Necco Wafer contained dry, circular discs, which came in a rainbow of colors and flavors — chocolate, licorice, cinnamon, lemon, lime, orange, wintergreen and clove.

The brand was advertised at concession stands in the 1950s, with signs featuring cheesecake pin-up type women that resembled Marylin Monroe. By the 1980s, the once ubiquitous candy began to disappear from concession stands. Joe Bartake wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News that he should assemble a survival kit that "consists of the kinds of foods not usually available at the new, streamlined concession stands — apples, oranges, peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, Necco wafers, etc." Necco not only lost its grip in theaters, it disappeared from any kind of shelf altogether in 2018, before the Spangler Candy Company of Ohio revived it two years later.

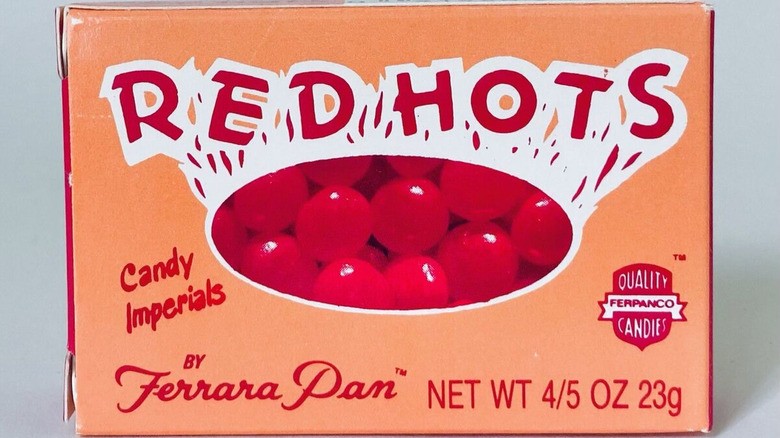

Red Hots

Cinnamon-based candies were some of the early confections consumed by patrons sitting in any kind of theater. Little red round ones known as Cinnamon Imperials were even recommended for Opera-goers as far back as 1871 "to perfume the breath" (via The Baltimore Sun). The term "Red Hot" was a nickname applied to hot dogs since at least 1835, and was pluralized for a new take on Cinnamon Imperials that was launched in the 1930s by Ferrara Pan Candy Company.

These little hard candies contained quite a spiced punch once the teeth penetrated the outside shell, and required a chaser of fountain soda to cool things down a bit. Actress Sissy Spacek was a fan growing up, and they were a still a popular seller at theaters in the 1980s, alongside Fun Dip, M&Ms, and Reese's Pieces. Today, you're more likely to find red hot-hot dogs at the concession stand than the boxed candy.

Sugar Babies

The James Welch Co. brought a caramel-on-a-stick candy to market in 1925 called Papa Sucker. Taking advantage of the popular phrase "Sugar Daddy," the slow-sucking candy was renamed as such seven years later. In 1935, Daddy had a child — Sugar Babies, which had the chewy caramel turned into bite-size candies with a candy shell. And yes, for a time, there was even a Sugar Mama, which was the same but covered in chocolate.

Fame film critic Roger Ebert loved munching on popcorn and Sugar Babies simultaneously, although his television co-host didn't share the same enthusiasm for them. In a 1995 interview with Frank Bruni for Fort Worth Star-Telegram, famed critic Gene Siskel said that if hell had a movie theater with only one candy available at the concession stand, that dishonor belonged to Sugar Babies.

SweeTarts

Sugary-sweet confections were a staple of St Louis' Sunmark Corporation. It found success in the 1950s with the colorful powdery Lik-m-aid pouches (now better known as Fun Dip), but due to its messy nature, funneled the grainy sugar into a straw tubular farm with Pixy Stix. The next genius, less mess, and theater-friendly evolution was turning Pixy Stix into tablet form, and that's how SweeTarts came to be.

In the days where there were so many candies at concession stands, like the 1980s, there were tiers. Higher priced ones included Jordan Almonds, middle range ones included Milk Duds, and the lower ones were reserved for more sugary ones like Hot Tamales, Lemon Drops, and SweeTarts.

In 2004, SweeTarts were still a movie draw. They were even used as a freebie carrot to lure parents to take their kids to see screenings of "Elf" in suburban Detroit.

Tootsie Rolls

Leo Hirschfield borrowed his daughter Clara's nickname "Tootsie" for his new hand-rolled chocolate penny candy that launched in 1896. These Tootsie Rolls eventually would be rolled into stores, newsstands, and movie theaters in various sizes.

Chocolate-flavored Tootsie Rolls had been a candy option since the silent movie era. Out of This ShoWorld columnist Barney Glazer said in 1958 that he enjoyed both Tootsie Rolls and Necco Wafers in those bygone days. Tootsie Rolls were advertised in the 1950s as a long lasting candy that was "a double treat at double features."

While the Tootsie name has branched out into fruit chews and lollipops, they have sadly left concession stands. Today, the brand is currently the steward of other famous candies that once were movie go-tos, like Charleston Chews, Dots, Sugar Babies, and Crows, although its Junior Mints property is still holding court with theatergoers.

Turkish Taffy

Turkish Taffy is neither Turkish in origin, nor actual taffy. The nougat-like confection was invented by mistake when Austrian immigrant Herman Herer used too many egg whites when crafting marshmallow candy. The candy was very breakable, with the package instructing eaters to "Smack it. Crack it." After being sold under the brand M. Schwarz & Sons, the Bonomo family assumed stewardship in 1936, and their good name still graces packages of Turkish Taffy to this day.

Turkish Taffy may not be as well-known of a product today, but is remembered by generations past, including being mentioned in Stephen King's "The Stand" and "The Dark Tower II," and the title of a Blue Oyster Cult song. Ron Wiggins opined about enjoying it as a kid at the movies in a 1985 The Palm Beach Post piece, saying, "Whatever happened to Bonomo's Turkish Taffy? What fool took it off the shelves? I preferred the banana. A plank would last you through most of a Saturday morning cartoon carnival at the Lyric Theater."