Old-School Grocery Store Chains That Were Forced To Close For Good

Back in the day, grocery shopping felt like visiting an old friend. You could stroll into your local grocery store, you knew your way around the aisles with your eyes closed, and there was always a friendly face ready to help find that one can on the top shelf. The shelves weren't stocked with a dozen different kinds of oat milk or fancy, schmancy $15 olive oil.

In the second half of the 20th century, the supermarket boom led to a bunch of regional chains popping up all over the country, each with its own loyal fans and quirky features. These stores started out small, but over time, many of them became the most popular grocery stores in the area. As time passed and the shopping landscape evolved, some of these chains survived, but most didn't. Consolidations, buyouts, and big-box competition drove most to extinction. Sadly, all that's left of the old stores are faded signs, empty storefronts, and Facebook posts asking, "Does anyone else remember this place?"

So, before you scan your own groceries at a self-checkout kiosk, pour one out for the supermarkets that didn't make it. Just don't spill it in aisle three because chances are, there's no one around to help clean it up.

A&P

A&P was the grocery store that transformed the way America shopped. Founded in the 1800s, it grew from a modest tea and coffee merchant into a retail juggernaut that reshaped the entire supermarket landscape. At its peak, A&P operated more than 15,000 stores, making it one of the largest retailers in the country and the place where generations of families bought nearly everything they needed.

But nothing lasts forever. A&P failed to adapt fast enough once its competitors began reshaping the space. Instead of innovating, A&P doubled down on old models and expensive acquisitions such as Pathmark, Waldbaum's, and Farmer Jack. Having already filed for bankruptcy in 2010 and shuttered a long list of stores, its second filing in 2015 was the final nail in the coffin. A&P liquidated its assets, and the supermarket that everyone had grown to love finally closed its doors for good.

A&P was definitely an era, a supermarket giant that shaped how generations of Americans shopped and thought about groceries. And when it fell, it signaled the beginning of the end for the old-school supermarket as we knew it.

Waldbaum's

Waldbaum's was like the friendly neighbor of supermarket chains. It was founded in Brooklyn in 1904, and the brand grew into one of New York's largest supermarket names, with Julia Waldbaum — the wife of one of its founders — serving as the face of the store. She appeared in ads, branded packaging, and shared her own home recipes. She once famously joked that the only products she wasn't on were dog food and toilet paper. She would visit stores and carry out small tasks, such as fixing produce displays, and even insisted that her home phone number remained listed because she wanted customers to know she was a real person.

Sadly, that level of care didn't survive the corporate takeover. When A&P bought Waldbaum's in 1986, it slowly eroded what made the store so special in the first place. The chain lost its charm, quality declined, and it faced sanitation issues. In the 1990s, the company became entangled in a messy dispute with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters amid claims that it had made dodgy deals with an organized crime figure, which led to low pay for employees. Waldbaum's officially closed in 2015, when A&P went bankrupt. Many of its Long Island stores were sold off to Stop & Shop.

Alpha Beta

Alpha Beta got its name from founder Albert Gerrard's oddly brilliant idea to arrange products on shelves in alphabetical order. It sounds chaotic now that we have aisles and sections, but back then, it helped customers find what they were looking for. In Southern California, the store expanded into a suburban institution, eventually spreading to more than 300 locations.

The store was a pioneer for grocery store chains, having made bold operational moves such as utilizing automated sorting and air freight for fresh fruit. It was even the reason stores and parking lots today aren't full of stray carts, having set a precedent by introducing shopping cart corrals. A great thing, because while no one realized it at the time, we now know that the average shopping cart is much dirtier than anyone thought. Alpha Beta basically defined what a modern grocery store should be.

Then, in 1979, Skaggs Cos. Inc. acquired American Stores Co., which included the Alpha Beta chain. Later, antitrust regulators forced the sale of large portions of Alpha Beta to Food 4 Less. The rest eventually merged into Lucky. Finally, in 1994, Ralphs announced a $2.5 billion merger that completely erased the Alpha Beta name. In the end, the brand faded, and today most shoppers have no idea how much of the modern grocery store experience — down to the carts in the parking lot — was shaped by this supermarket chain with an alphabetical shelving system.

Bohack

Bohack was one of those New York institutions where most people seemed to know someone who worked there. These were neighborhood supermarkets spread across every borough and Long Island, serving as part grocery store and part daily social hub. Clerks knew customers, and the customers knew each other. Its founder, H.C. Bohack, opened the first store in 1887 and spent decades expanding across NYC, eventually building production warehouses, gas stations, and restaurants. The brand was so popular at that time that it even appeared in the film adaptation of "The Odd Couple."

However, a highly ambitious expansion plan ultimately sank the company. After the company went public in 1965 and Charles Bluedorn of Gulf and Western Industries became the majority shareholder, Bohack began rapidly buying up other supermarket chains. The recession of the 1970s hit just as the company had stretched itself too thin, leading to multiple bankruptcies.

Bohack finally closed for good in 1977. In a post on the blog Blah Blog Blah, a family member of H.C. Bohack commented with fond memories about the store. His whole family worked there, but he was too young, and it "was a [rite] of passage" that he never got to experience.

Jitney Jungle

Jitney Jungle was a Southern grocery brand born in Mississippi in 1919. The chain survived basically every major American economic disaster you can think of. It endured recessions, World War II, the Great Depression, inflation cycles, and decades of fierce supermarket competition in the Gulf South region. Through all that, it remained a private company people knew and loved.

In the 1990s, Jitney Jungle was acquired, which was the beginning of its decline. The new owners piled the company with so much debt and then made things even worse by acquiring Delchamps just a year later, adding even more debt. This debt, along with tons of new competitors opening in its markets, meant that even this decades-old supermarket couldn't survive.

By 1999, just years after its acquisition, Jitney Jungle had entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy. By the end of the bankruptcy auction, stores were sold off in pieces to Winn-Dixie, Bruno's, Brookshire Bros., and others. By 2001, a chain that had withstood generations of American history disappeared. Jitney Jungle is an excellent example of a company that was loved by many, not dying from a lack of loyalty, but from corporate-driven greed, financial decisions, and debt that it would never have created for itself.

Red Owl

Founded in 1922, Red Owl started as a grocery, dry goods, and coal store. There was a point when more than half of Minnesota's groceries were sold in Red Owl stores, and it pioneered big-box layouts, self-service packaged meat long before they became the norm. The latter might not match the quality of butcher shops, but you can't deny the convenience.

Even after the brand disappeared when SuperValu bought it out in 1988, it remains a fond memory for those who worked there. "It's unusual in today's marketplace to say you love your employer, but we did," a former employee told the Star Tribune in 2018. That kind of loyalty says everything about what Red Owl meant to people. The store was like family.

While the official Red Owl supermarkets are long gone, one small store still carries the name. Mason Bros. Red Owl in Green Bay isn't part of the original chain, but an independently owned store that was purchased from Red Owl in 1969 and kept its sign when the brand was dissolved in 1988. Today, it stands as the last reminder of a grocery era built on community.

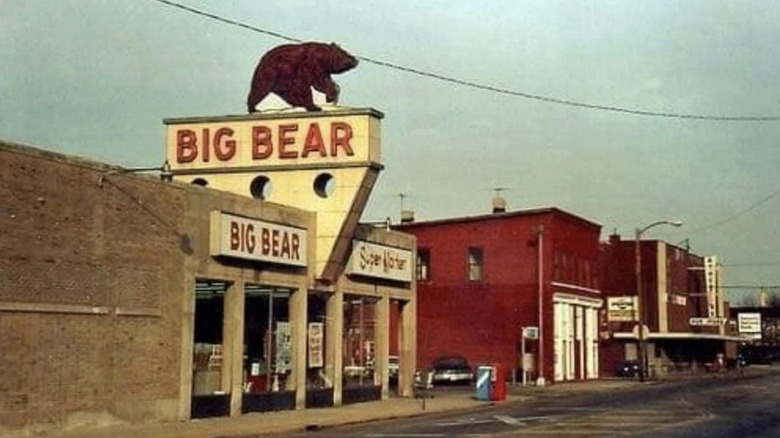

Big Bear Stores

Long before grocery stores used cartoons as mascots, Big Bear had a real, live trained bear at the store. The Ohio-based chain got its start in 1934, when founder Wayne E. Brown opened the first self-service supermarket in a converted roller rink in Columbus. At Big Bear, customers could grab their own items instead of asking a clerk. This felt groundbreaking at the time, and executives swore people would start stealing.

We don't know whether people stole or not, but it's safe to say the bold move paid off. Within three days of opening, it attracted more than 200,000 customers. That single location grew into a regional chain with over 60 stores.

Big Bear became one of the Midwest's defining supermarket chains, pioneering ideas that are now industry standards, such as wide aisles, center-store produce, money-back guarantees, and even free parking. When it went bankrupt in 2003, it left behind decades of grocery innovation, as well as one of the most memorable mascots in supermarket history.

Food Fair

Food Fair started as a neighborhood grocery in Pennsylvania in the late 1920s and grew into one of America's biggest grocery store chains, operating over 500 stores. By the 1960s, the supermarket was buying up smaller grocers and experimenting with a new name, Pantry Pride.

But it seems like the company expanded too fast. By the late 1970s, Food Fair was deep in debt. It filed for bankruptcy a few years later and began selling off parts of the business, shutting down its J.M. Fields department stores, and rebranding the remaining Food Fairs as Pantry Pride stores. After shedding stores and restructuring, the company tried to emerge from bankruptcy in 1981 under the name Pantry Pride Stores, Inc., with a new headquarters in Fort Lauderdale. But despite the fresh start, the company never regained its old strength.

In 1985, investor Ronald Perelman and his firm MacAndrews & Forbes took control of Pantry Pride and famously used it to buy Revlon, marking the end of its grocery days. In the 1990s, its final remaining Florida stores were sold to Fleming Companies. By 2000, both Food Fair and Pantry Pride had been shelved for good.

Daylight Grocery

You hate to see these kinds of stores disappear, especially the small regional ones that felt like such a big part of the community. Founded in 1928 by Israel Edwards and David Lasarow, Daylight Grocery began as a single neighborhood market in Downtown Jacksonville. Even during the uncertainty of the Great Depression, when many businesses struggled, Daylight managed to grow, opening a second store by 1931 and operating a dozen stores by 1950.

By the 1970s, even after decades of expansion, the small regional chain was struggling to keep pace with the arrival of large national grocers moving into Florida. Locations slowly disappeared, and by 1980, it had just four stores. When its last store in Jacksonville closed its doors, it marked the quiet end of a 60-year run and one of the city's earliest supermarket success stories.

Farmer Jack

Farmer Jack was the kind of grocery chain every Metro Detroit family knew. However, before it was known by that name, it was a small butcher shop called Tom's Quality Meats, which was started in 1924 by Jewish-Russian immigrants Tom Borman and Sam Burlack. Business was good enough that Borman's brother, Al, opened a second location. Soon enough, the Bormans were running a growing grocery empire under the name Borman Food Stores.

By the 1960s, it had built a reputation around Metro Detroit, and in 1965, it launched a new concept called Farmer Jack, adding home goods, garden supplies, and that friendly, all-in-one neighborhood feel. Through the 1990s, Farmer Jack seemed unstoppable, topping 100 stores and becoming A&P's (which bought Farmer Jack in 1989) most profitable brand. But as competition intensified and rivals slashed prices and modernized their stores, Farmer Jack struggled to keep up. Expansion beyond Detroit stretched the brand too thin, and in 2007, the last locations closed their doors for good. Today, a handful of empty former storefronts still linger around Detroit.

Delchamps

Founded in Mobile, Alabama, Delchamps grew from a small local grocer into a success across the South. By the 1990s, it operated nearly 120 stores across Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

But you probably already know where this is headed. Like so many other beloved regional chains, Delchamps was acquired by a larger player that promised to strengthen it, only to mismanage it straight into extinction. That player was the Mississippi-based Jitney Jungle (if that name sounds familiar, that's because it's another supermarket on this list that didn't make it), which acquired Delchamps for around $215 million in 1997, claiming it would create a stronger competitor in the Southern states.

However, the merger that was supposed to save both chains sank them instead. The deal doubled Jitney's debt, and within just a few years, both brands were struggling to stay afloat. By 2000, Jitney Jungle had filed for bankruptcy, and Delchamps' remaining stores were sold off or shuttered.

Eagle Food Centers

Eagle Food Centers started out the way so many of these once-beloved regional chains did — as a small, family-run grocery store dedicated to serving its neighbors. Founded by the Tenenbom family all the way back in 1893, it gradually grew into a true Midwestern staple, operating 136 stores across the region at its peak and bringing in $1.2 billion in sales. As self-service emerged as the future of grocery shopping by the 1930s, Eagle adapted early and lowered prices to stay ahead of the curve.

The supermarket was known for its one-stop convenience, where you could find everything from pharmacy services to baked goods under one roof. And honestly, the baked goods alone were probably enough to draw plenty of customers, because we all know that grocery store cakes just hit different. However, by the early 2000s, the cracks had started to show. After years of losing money and trying everything to sell the company, Eagle threw in the towel and filed for bankruptcy in 2003, closing or selling its remaining stores and ending the run for the century-old Midwestern name.