Why British Food Became Known As Boring And Bland

There is a joke about heaven and hell, and the positions various European nationalities would fill in each; it's a bit too involved to tell here, but the gist of it is that, in hell, the cooks are English. Few cuisines are as maligned as British cuisine, which gets attacked on a few different fronts. There are some strong-tasting foods which repulse unsuspecting diners, such as Marmite, and there are dishes with eyebrow-raising (if not stomach-turning) ingredients, such as haggis and blood pudding (the kind of pudding that was originally referred to in the saying "the proof is in the pudding"). But the prevailing complaint has to do with its perceived blandness — unlike garlic-rich Italian food or sauce-laden French food, British food is simple, unadorned, and, to some, quite boring. Why is that the case? Part of it has to do with the priorities of British cuisine, but another part of it has to do with the Industrial Revolution and two world wars.

Before the Industrial Revolution, Britain had a working class culinary heritage every bit as rich as those in Spain, Italy, or France. Consider Cornish pasties, handheld beef and onion pies perfect for those working the tin mines of Cornwall; the Lancashire hotpot, a lamb and onion stew baked in an oven; and the many different cheeses of Britain, including cheddar and Stilton. But the Industrial Revolution (which originated in Great Britain, after all) shifted the focus from handcrafted artistry to mass production. Meat pies and cheese were still made, of course, but they were made on an industrial scale, one which valued efficiency over flavor.

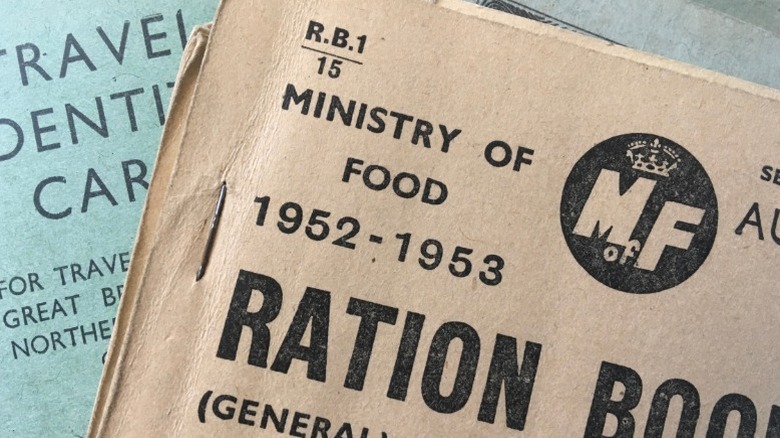

War rationing didn't help Britain's culinary reputation

For a time after the Industrial Revolution, the aristocrats and other wealthy British people still relished fine food (the good folk of "Downton Abbey" certainly weren't eating beans on toast at their fancy dinners, were they?). But, when World War I came along, not only were the best ingredients rationed or unable to be imported, most of the (male) cooks and servants who made those meals were drafted into the war effort and sent to fight in mainland Europe. Thus began a process of devolution that sped up even further when, 20 years after the first World War ended, a second one began — this one involving direct attacks on the British isles.

Although the war ended in 1945, rationing didn't end in Britain for another nine years after that. This meant that, while Britain's former colony of America sprinted headlong into a postwar world of prosperity and TV dinners, the British populace had limited resources, with rationed foods including meat, sugar, and even bread. Thus, British households learned to make do with what they had, stretching ingredients as far as they could and avoiding any unnecessary flourishes. For example, one of Paul McCartney's favorite childhood snacks, sugar sandwiches, came from rationing. Once rationing ended, and the influence of Britain's Indian and Afro-Caribbean populations began to make itself known, new life was breathed into British cuisine.

British food has long been on the simple side

With all that said, it's only part of the story. After all, France and Italy were both devastated by World War II, but their cuisines are still seen as lovely and flavorful, in marked contrast to Britain's. Why is that the case? Well, to a certain extent, the shoe does fit: Traditional British food is, in fact, on the simpler side when it comes to flavor. There are a few different reasons for that. First, while plenty of spice flowed into Britain during the British Empire's heyday, it eventually went from a status symbol for the wealthy to something the common man could get his hands on. That meant there was a reaction against heavily spiced food among the upper class, whose members began to favor "natural flavors."

Another possible reason has to do with that famous stiff upper lip. At the risk of engaging in some reductive national stereotyping, British culture is often seen as more reserved and less welcoming than, say, Spanish or Italian culture (perhaps French culture had the same problem, but we're given to understand Juliette Binoche swept in and opened people's hearts with the power of chocolate). As such, British food is often more functional than a day-long labor of love. Then again, if you ever have a good Sunday roast, you know how great "functionality" can taste.