How A Failed Contest Incited Riots, Killed 5, And Turned An Entire Country Against Pepsi In The '90s

In 1992, Pepsi came up with a brilliant idea for a contest it would run in the Philippines. The idea was to print numbers on the inside of Pepsi bottle caps, then every weekday evening they'd read out a number on air. If a person had a winning number, they'd receive cash prizes — most of which amounted to around $5. This contest, dubbed "Number Fever," quickly rose to raging popularity and people would tune in every night hoping their number would be called. There was one number that everyone wanted, though: the grand prize.

Two caps were printed with a grand prize number one them. The contestants who found the winning bottle caps would be given 1 million pesos, the equivalent of $68,000 at the time. These numbers included a security code for verification purposes, much like the 50,000 prize numbers handed out up until that point. It seemed like a profitable, straightforward business idea that mirrored past contests. This time, however, things went horrifyingly wrong as multiple people wound up dead.

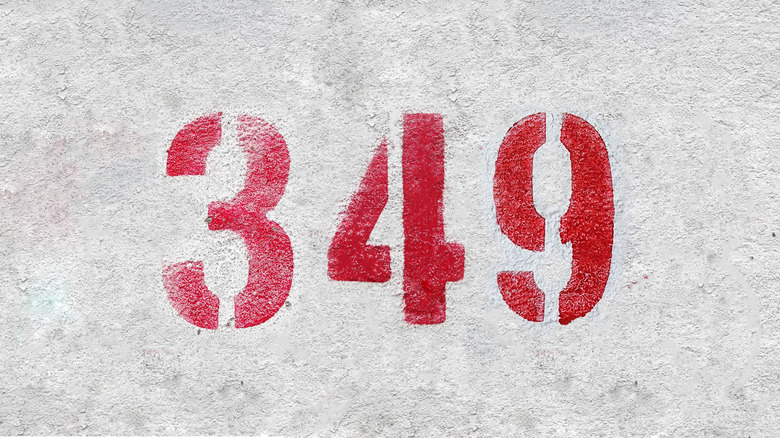

Everything took a disastrous turn on May 25, 1992 when a whopping 70% of the country tuned in to hear the grand prize be called. Anticipation swelled amongst the families who saw the money as life-changing (and potentially life-saving). At the big moment, the announcer read out the number 349. Rather than two people cheering in celebration, hundreds of thousands of people leapt to their feet to celebrate their grand prize win. Unbeknownst to them (or Pepsi), 800,000 bottle caps listed that number. What came next was one of the biggest moments in Pepsi history and one of the worst PR blunders.

How did Pepsi's dire mistake happen?

The reason this occurred in the first place was because Number Fever had gotten so popular. Initially, the contest was supposed to run for a limited time, but the success caused Pepsi to extend the promotion by five weeks. Because of this, the company had to add new numbers even though it'd already printed and distributed the two grand prize ones. The computer continued to print the winning number without the security code and without Pepsi realizing its mistake. By the end, the printing computer had created $32 billion worth of 349-labelled bottle caps. Other Pepsi disasters, such as the Pepsi Point fighter jet fiasco and Pepsi recalls that impacted millions, had been problems. This had the potential to ruin them entirely.

More than 486,000 people showed up at the Philippines' Pepsi bottling plant to claim the prize, which is when the company realized they'd made a dire mistake. Executives called a meeting at 3 a.m. to discuss what to do. They agreed there was no possible way they could pay everyone the grand prize amount. (A payout of that magnitude was more than half the GDP of the Philippines that year.)

A plan was hatched to offer everyone with a 349 number 500 pesos as a gesture of goodwill, a far cry from the million originally promised. Only those with the proper security code would get the grand prize. Pepsi announced there had been a computing error and hoped that would be the end of it. A good number of people accepted this offer and about $10,000,000 was paid out. Others, however, did not — and things began to get violent.

The aftermath of one of Pepsi's biggest mistakes

By 1993, a boiling point had been reached with people enraged over being cheated out of their winnings. Many said that the promotional materials had not mentioned a security code and that Pepsi was going back on its promise. Pepsi's revenue temporarily plummeted. Boycotts were staged and protests were held outside of factories and executives' homes. Many factories were forced to put up barbed wire fences to prevent vandalism or worse.

At its height, rioters used grenades and other bombs against trucks transporting Pepsi products. 37 trucks were attacked, causing many Pepsi delivery drivers to not show up for work and armed guards became their replacements. One grenade meant for a truck went astray and ended up killing a schoolteacher and a young child. Three Davao warehouse workers also died due to an explosive lobbed over the barbed wire fence. Execs received constant death threats from an impoverished populace who had believed, for one brief moment, that they'd found a way out.

Legal battles raged in the courts for two decades, with some people winning small sums for their troubles and many others having their cases thrown out. 22,000 people in total sued Pepsi while the Department of Trade and Industry fined the company 150,000 pesos for violation of promotional conditions. The last case was thrown out in 2007 by the Supreme Court of the Philippines with a final ruling that the matter was now closed. (The U.S. Federal Trade Commission sued Pepsi years later, but that's another story.) Today, the term "349ed" is used in the Philippines as a term for getting fooled.