The Only Recap Of Big Boy's Downfall You Need

Now reduced to several strings of outlets with a moderate presence in a few far-flung regions, Big Boy is not the restaurant chain it used to be. Big Boy started in Los Angeles in the 1930s (as Bob's Big Boy) and grew into a national network by the 1950s, operating as a drive-in, early fast food spot, family-style diner, and casual dining establishment at different times. Like many other chains that enjoyed explosive growth in the mid-20th century, Big Boy's fare mainly consisted of grilled hand-helds, like hamburgers.

It made one innovation in particular, a burger so new and different — and eventually, phenomenally popular — that the chain bore its name: the Big Boy. The first major double-patty, three-bun burger in the U.S. (debuting years before McDonald's signature burger, the Big Mac), the Big Boy was also the name of the restaurant's adorable, omnipresent, and influential food mascot: a cherubic, grinning child in overalls.

Formerly a household name in fast food, or something like it, Big Boy has been reduced to a once-popular chain restaurant that now barely exists. Here's the story of how Big Boy became a major pioneer and purveyor of large burgers, and how it all almost completely faded away.

Big Boy was built on a big burger

Before the age of national fast food restaurant chains, Americans could get a quick, cheap meal at a lunch counter — tiny diners where short-order cooks made burgers, sandwiches, soups, and other simple dishes. Bob Wian had worked at many of those establishments, and when one in Glendale, California, called The Pantry, went up for sale in 1936, he sold his car to get the money to make the purchase.

Eventually renamed Bob's Pantry, it did brisk business, but success would truly arrive after Wian's attempts at creating a new kind of hamburger led to something special. When a regular reportedly asked Wian to come up with a new burger just for him, Wian sliced a bun into three sections instead of two, allowing space for two hamburger patties. Along with his special burger sauce and the usual burger accoutrements, Wian had invented "The Double-Deck Hamburger." The extra-large burger got its final name thanks to a child who worked at Bob's Pantry. Wian couldn't think of the kid's name one day, so he called six-year-old Richard Woodruff "Big Boy." That's what he called the burger, too.

Big Boy was the first big California chain

Within a few years of opening the first Bob's Pantry, demand was so massive for the Big Boy burger that Bob Wian expanded the operation with multiple Bob's Big Boy Drive-Ins. He was right to rename his restaurants after his signature and novel menu item, because it brought in hundreds of customers every day. Each location featured uniformed waitstaff and three cooks perpetually on the clock, preparing 300 Big Boy burgers every hour.

When the U.S. entered World War II and the war efforts led to labor and meat shortages, Wian shut down one of his original four outlets in the Los Angeles area. Fortunes recovered and expanded after the war, and in 1949, the flagship (and still standing) Bob's Big Boy sit-down restaurant was built in Burbank. A large space with a dining room and outdoor patio, it became a landmark and was officially listed as a Point of Historical Interest in the state of California. It was a great place to spot celebrities — cult filmmaker David Lynch had a lifelong love for Bob's Big Boy — and many movie scenes were filmed there. As of 1951, Bob Wian operated eight Big Boy restaurants in California, and just five years later, he had expanded to 12.

Big Boy was often just a burger at other restaurants

Bob's Big Boy would eventually grow into a national operation, but the original collection of Bob Wian's restaurants really only had one item that stood out from the competition's offerings: the Big Boy two-tiered hamburger or cheeseburger. In the late 1940s, when Bob's Big Boy was still in its early phase as a multi-unit California-only chain, Wian sold the rights to the Big Boy sandwich to two restaurant companies on the other side of the country. They both took on the name Big Boy because it was allowed under the terms of their contracts, establishing Eat'n Park Big Boy in Pittsburgh and Frisch's Big Boy in Cincinnati. Both restaurants and their spinoffs served a menu of their own design that also prominently featured the Big Boy burger from California.

The move was purely business for Wian — by gaining a foothold on the double-decker burger throughout the United States, he could obtain a nationally recognized and legally enforced trademark on his creation. That set the stage for Big Boy restaurants to pop up all over the country. More than 30 otherwise independent restaurant groups affiliated with Big Boy from the 1950s onward, each with a particular territory of the U.S., and each adding — as required by Bob Wian — their own name to their eateries.

Big Boy's founder lost the company lots of money

As Big Boy expanded around the country, founder Bob Wian made himself and his company a lot of money. However, he didn't necessarily believe in returning the profits to the company. As early as the mid-1950s, Wian offered employee benefits like health insurance and profit-sharing. No worker was required to devote a portion of their paycheck to a retirement plan, because Wian directed 20% of Bob's Big Boy profits to pensions. Employees commonly retired with a nest egg worth several hundred thousand dollars.

Employees also got first crack at opening a Big Boy franchise of their own. That potentially lucrative prospect was already relatively inexpensive even to Bob's Big Boy outsiders. Franchise fees for new operators were nominal — $1 a year until the 1970s — and in exchange for marketing and branding, partners paid about 1 to 2% of their sales revenues back to Wian, a fraction of what other fast food companies charged.

For years, Wian missed out on vast sums of money for the Big Boy enterprise. Then in 1966, the company suffered a $3 million financial loss (or around $30 million updated for inflation) after the shrimping company Wian opened to supply his restaurants fell apart. The board of directors had had enough, and essentially gave Wian an ultimatum: leave the company he started or offload the whole endeavor. He went with the latter, selling Big Boy to the Marriott Corporation for $7 million.

Big Boy changed hands as it slipped into irrelevance

When it bought Big Boy, the Marriott Corporation operated more restaurants in the U.S. than any other company. At various times, its portfolio also included the Hot Shoppes diner chain, Farrell's Ice Cream Parlour, Roy Rogers, and Gino's Hamburgers. By the end of the 1970s, Marriott oversaw Big Boy as it peaked with more than 1,000 outlets across the United States. The chain was most dominant in California, Michigan, and Ohio, where franchisees ran around 100 restaurants in each state.

Marriott struggled to effectively run Big Boy or make it as profitable as it could've been. As the 1970s and 1980s wore on, the rise of fast food began to supplant the diner and drive-in culture of the mid-20th century. National chains introduced the idea of a consistent menu across locations, with the same offerings, quality, and familiar taste. Due to Big Boy's unique agreement with its affiliates, franchisees could populate their menus with whatever they wanted, so long as they sold the Big Boy burger, which was significantly less thrilling to customers who could get a similar sandwich at McDonald's by then.

Having already begun dabbling in hotels in the 1950s, the Marriott Corporation moved out of the restaurant management business in favor of room rentals. In 1987, it offloaded Big Boy to the Elias Bros., one of Big Boy's first and most successful franchisees.

Big Boy went bankrupt

Once just one of many Big Boy franchisees, Michigan-based Elias Bros. Corp. was in full control of the entire Big Boy corporate operation by the 1990s. The ownership group endeavored to make Big Boy bigger, acquiring and rebranding the 34-unit Shoney's chain in late 1998. That project took more time and money than previously projected, and Elias Bros. wound up facing mounting debts so extensive that it had to negotiate new financial terms with vendors.

Even after the botched expansion was settled, Big Boy still faced major financial problems, such as not having enough operational cash. In a move to end the downward spiral, Elias Bros. shut down 43 Big Boy restaurants in Michigan, Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Business was solid at what locations remained, but just weeks after closing about 10% of its restaurants, Elias Bros. filed for bankruptcy. In addition to seeking Chapter 11 protections to enable financial restructuring, the company also said it would immediately unload all 455 Big Boy outlets in its control to investor Robert G. Liggett Jr.

Big Boy affiliates dropped the name in huge numbers

After the Marriott Corporation acquired the Big Boy machinery, it changed the way the franchise system operated so it would be more financially beneficial. Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, that franchise system broke down, and multiple major Big Boy operators chose to disaffiliate from the brand. Eat'n Park Big Boy, the territorial representative in western Pennsylvania, chose not to renew its contract in 1975. While the company acknowledged that the drive-in format it still utilized was increasingly passé, it was upset that Marriott discontinued Wian's $1 annual franchising fee.

JB's Big Boy ran restaurants in 16 states, and when Marriott wouldn't allow it more territories, it sued in 1984 to break its contract. The case was settled, and JB's ultimately paid $7 million to remain with Big Boy, buying another 29 company-owned restaurants. Just four years later, JB's let its contract expire because it objected to the $1 million in annual franchise fees Marriott planned to levy. Just like that, 110 JB's Big Boys became just plain JB's.

In 1984, Big Boy lost its biggest franchisee when Shoney's Big Boy paid a $13 million fee to void its contract — the group wanted to expand, but could only do so into established Big Boy territory. That instantly unbranded 392 Shoney's Big Boys, making them just Shoney's.

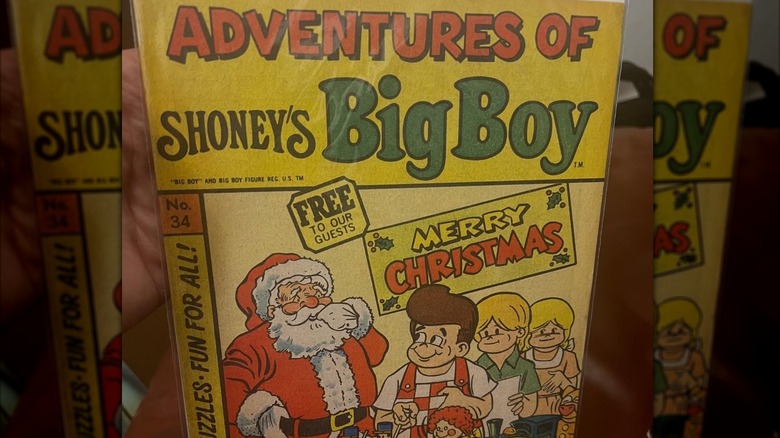

The end of a Big Boy comic book was a turning point

No matter who owned any given Big Boy restaurant, they also got the right to distribute a company-commissioned comic book called "The Adventures of Big Boy." Free of charge and geared toward kids, it was a precursor of the kids' meal prize that would become standard in fast food. The comics depicted the imagined cartoon adventures of Big Boy, the chain's burger-loving child mascot designed by artist Ben Washam, which appeared on lots of other licensed merchandise and was based on the child who inspired the Big Boy name, Richard Woodruff.

Timely Comics printed the first "The Adventures of Big Boy" comic in 1956, and the initial 12 issues were written by future Marvel Comics talent Stan Lee. Also including games, puzzles, and letters from readers, "The Adventures of Big Boy" was one of the most widely distributed comic books and children's magazines in the world, peaking at 1.2 million printed copies of the July 1980 edition.

When Big Boy called off "The Adventures of Big Boy," it was the end of an era, both for comic books and for the chain itself. Issue No. 466 was published and sent to the 800 or so remaining Big Boy restaurants in August 1995, and that would be the final issue ever made. Company brass felt the '50s throwback comic was too old-fashioned and no longer in line with its contemporary branding moves.

Big Boy got caught up in a COVID controversy

Controversy and closures are rarely a good sign for a restaurant in decline, and Big Boy endured both during the pandemic. In 1984, Joe and Bonnie Humphrey opened a Big Boy in Sandusky, Michigan, and they later ceded control to Troy Tank. He was in charge in the fall of 2020 when a sudden rise in COVID-19 cases led to another round of shutdowns to stop the spread of the disease, as had been done that spring. The state government required restaurants to close down public dining spaces, but Tank kept his Big Boy open. He reportedly adhered to the social distancing standards enacted during the pandemic, such as limiting occupancy to 50% of capacity and enforcing the use of masks for staff and customers.

When Big Boy Restaurant Group LLC found out that Tank had violated the law, it moved to cancel his franchise contract. "Big Boy has and always will be dedicated to the health and safety of our customers and staff," Big Boy's corporate office said in a statement (via WXYZ). "The actions of a franchisee in Sandusky, Michigan, are not representative of Big Boy as a brand, our operations, or standards." The Sandusky Big Boy not only lost its affiliation, turning it into Sandusky Family Diner, but it was also shut down by court order for a few weeks and fined. The rebranded restaurant closed down for good in 2024.

Big Boy attempted a rebranding

The words "Big Boy" likely make as many people think of the restaurant's mascot as they do the diner chain or its eponymous double burger. The animated character with red and white overalls and a pompadour hairstyle appeared on Big Boy's menus and marketing materials for decades, and was rendered as a statue outside some locations. The Big Boy is clearly an intrinsic, easily identifiable key to Big Boy's success, but in 2020, the restaurant's executive decided to get rid of the imagery that it had used for about 80 years.

Somewhat confusingly, the restaurant kept its entrenched name — Big Boy — but did away with its mascot — also Big Boy. In his place was a generically drawn little girl named Dolly, who was an obscure character from the "The Adventures of Big Boy," the in-house comic book that hadn't been published since 1995. Big Boy has also experimented with opening some restaurants under the name Dolly's Burgers and Shakes, but it hasn't been a resounding success.

Big Boy couldn't pay its bills

As of 2024, one of Big Boy's largest franchisees, Frisch's Big Boy, ran 80 locations, mostly in Ohio. But then it suffered from financial issues so severe that it neglected to pay $4.5 million in rent charges on its various restaurants. Some of those eateries were permanently evicted, and by 2025, Frisch's Big Boy's network was down to 30 entries.

Big Boy Restaurant Group LLC adopted the leases associated with troubled Frisch's-run spots. Looking like an old-school restaurant chain attempting a comeback, the company announced plans to open as many as 55 restaurants under the original Big Boy branding in June 2025. But then, Frisch's Big Boy filed suit. It alleged that such a move couldn't legally happen because Frisch's controlled the trademark on the Big Boy name in a territory that spanned Indiana, Kentucky, and parts of Tennessee and Ohio. In an instance of a restaurant chain spinoff that flopped, Big Boy opened six new locations in Dayton and Cincinnati under its Dolly's Burgers and Shakes concept, but closed them all down in October 2025.

If, and when, Big Boy Restaurant Group LLC ever follows through on that expansion plan, it would double the chain's imprint, as only 55 Big Boy restaurants are still open. There are a few in the chain's birthplace of California, as well as in Nevada, North Dakota, and Ohio, but the vast majority sell double-decker burgers across Michigan.