I Can Believe It's Not Butter: The Rise And Fall Of Margarine

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

You may not have seen the commercial in years, but you'd recognize the setup instantly. Sweeping chords play and a day-dreaming, bespectacled housewife sighs as the screen does that fuzzy flashback fade. There are quick shots of vaguely fairy tale locales—an Italian palazzo, stately fountains, a rose garden straight out of Beauty And The Beast—and our suburban soccer mom reappears in flowing gown and sparkling jewels. Then we pan to the best gem of all: Fabio with his golden mane and an accent so stereotypically exotic you might cry at the TV, "I can't believe!"

Whether the cheesy romance shtick tapped into repressed urges of middle-aged women or customers were swayed by the mounting health warnings against cholesterol and saturated fats, the Italian model helped sell a lot of margarine in the '90s and pushed I Can't Believe It's Not Butter! to the top of the category. Today, though, margarine's role in the kitchen has diminished. The one-time star of healthier eating has lost much luster as America's love for processed food wanes in favor of the full-flavored, "real" foods of yore. Even Unilever—the maker of America's two top margarine brands, I Can't Believe and Country Crock—is exiting the margarine business, selling its suite of spreads this past December.

How did mighty margarine climb so high only to fall?

Margarine’s rise

Though butter's history stretches over millennia, margarine is a relative newcomer, dating back only to the 19th century and Europe's industrial revolution. At the time, oils and fats of all kinds were in high demand and the continent's citizens were moving from agrarian fields to cramped (and growing) cities. Butter prices doubled between 1850 to 1870, and, in looking to lower costs of feeding his armies and provide relief to his people, French Emperor Louis Napoleon III offered a cash prize for developing a cheaper alternative.

Enter Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès. In addition to having an absolutely fabulous name, this monsieur was a prolific chemist working on syphilis remedies, leather tanning, bread baking, and—most importantly for our purposes—fat processing. Building on the work of his patron and mentor Michel Chevreul, Mège-Mouriès patented a new product called oleo-margarine and took home the cash purse in 1871.

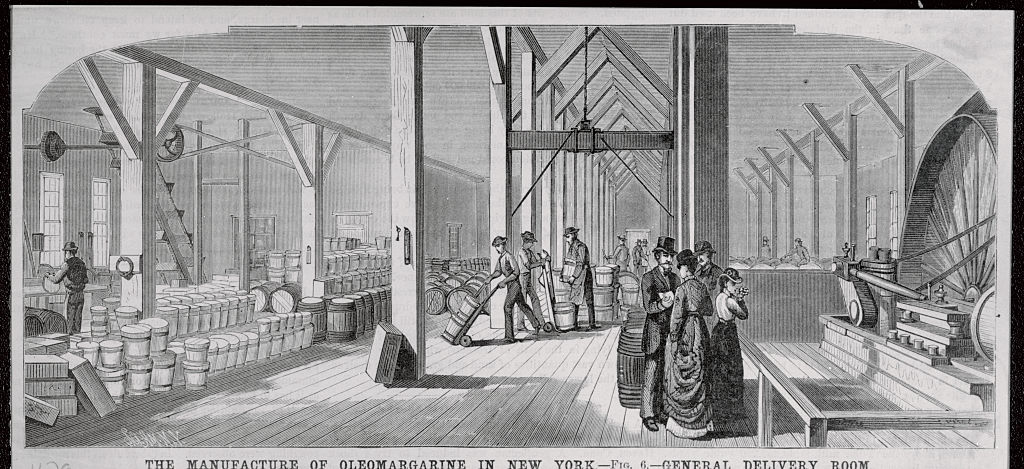

Oleo-margarine got its name from beef tallow (oleum, in Latin) and an animal fat extract called margaric acid that formed pearl-like drops (margarites, in Greek). When mixed with salted water and skim milk, the result is an edible solid that is just as fatty as butter, though not as flavorful. The beef fat base may seem strange to modern sensibilities—no margarine today uses tallow, and everyone has dropped the "oleo" prefix—but this practice was born out of necessity; plant oils remain liquid at room temperature and can't be used on their own to form a solid stick like butter. It wasn't until the early 20th century that new technology allowed margarine to switch to a cheaper (and more shelf-stable) vegetable oil base.

Mège-Mouriès' creation was a dull white hue—butter's pleasing yellow color comes from pigments in the grass that cows graze on—and lacked the satisfying complexity of what we would consider quality butter today. But it did fill an important niche.

"Margarine's appeal, especially in its early days during the late 1800s, was not only about its relative affordability compared to butter, but also margarine's quality and availability," said Elaine Khosrova, author of Butter: A Rich History. "Butter back then (and for most of its unrefrigerated history) could be a very dodgy perishable product—sour, rancid, over-salted, dirty, moldy, and even filled with stones and root vegetables to give it weight." Add to this that butter was a seasonal product (cows which give birth in the spring will stop producing milk by the winter) and the convenience and reliability of a manufactured product like margarine becomes clear.

The battle against Big Dairy

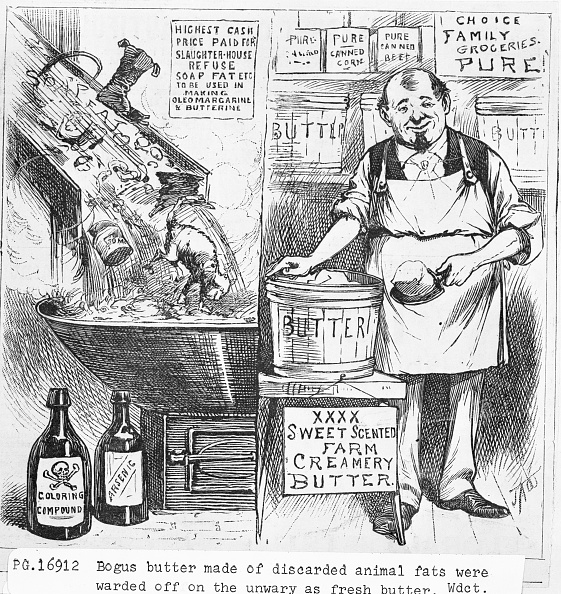

Margarine crossed the Atlantic and quickly spread throughout the U.S. As it was cheaper to produce than butter, unscrupulous dealers realized that it could be passed off for the real deal (at real butter prices, of course), leading to as much as 60 million pounds of "bogus butter" sold stateside in 1885 alone. Big Dairy sensed the danger of this competitor and stepped in, first lobbying the public with a smear campaign to ruin margarine's reputation, then lobbying Congress and state legislatures to stop or limit its sales. Scandalous claims appeared in newspapers and political cartoons (Candles, cats, and rubber boots used in manufacture! Margarine linked to insanity!) and dairy farmers (and their elected representatives) passionately fought for "sweet and wholesome" butters.

In 1886, the U.S. passed the federal Oleomargarine Act, which imposed heavy taxes—two cents per pound—plus restrictive licensing and fees for dealers. Individual states went even further: 32 states made it illegal to dye margarine yellow, eight banned it outright, and one, New Hampshire, allowed it to be sold only if it was dyed pink. The Supreme Court stepped in and overturned this most extreme law, stating, "To color the substance as provided for in the statute naturally excites a prejudice and strengthens a repugnance up to the point of a positive and absolute refusal to purchase the article at any price."

Despite the extensive legislation, enforcement of margarine restrictions was difficult and interest in the artificial substitute grew. During World War I, rationing of butter and animal fats accelerated the switch to plant-based margarine and made eating margarine a culturally acceptable—nay, patriotic—act. The Great Depression and World War II meant further belt-tightening, and by mid-century, margarine had overtaken butter in usage. According to the USDA, margarine was about a third the price of butter in 1946—23 cents for a pound of the artificial stuff versus 71 cents for the real deal.

But price wasn't the only draw. "Consumers in the '40s and '50s were ideologically smitten with the ever-growing selection of processed, packaged, standardized foods being offered them in new-concept supermarkets," Khosrova said. "In buying factory foods, homemakers gained ready-to-eat convenience as well as cultural status." Margarine wasn't just a pale substitute, but a modern marvel.

Federal restrictions and taxes were lifted in 1950, and states did away with their laws against coloring. The last hold out? Dairy darling Wisconsin in 1967.

Margarine’s fall

At the height of the margarine craze in 1976, annual American consumption reached 12 pounds per person compared with five pounds of butter. Margarine's popularity, however, has been falling precipitously since, and has accelerated over the last decade. Butter took back the lead over margarine in 2005, and today we annually eat less than 3.5 pounds of margarine per capita.

Though the industry is moving away from harmful trans fats, a certain stigma remains. Marketing is in flux, and most brands have dropped the term "margarine" all together, preferring to call their products a "spread." Recipes are also changing to produce lower-fat and trans fat-free versions, while some spreads are now made with naturally semi-solid oils like coconut or palm. Though these solutions yield margarines that can hold their solid shape, they are higher in saturated fat, undercutting some of margarine's old health claims.

Butter, meanwhile, is poised for a resurgence. Global sales are expected to increase another 9 percent by 2022, and butter is absolutely booming in unlikely markets such as China and Iran. Even McDonald's has switched from margarine back to butter.

The real boon, though, might be that eating butter is no longer thought to be as bad for you as it once was. "What's finally being redeemed is saturated fat itself," Khosrova said. "Now we know that there are different kinds of saturated fat (and in different proportions in meat, dairy, plant) and many that follow unique, synergistic and healthy, metabolic routes. A broad-brush nutritional prohibition on saturated fat is not only erroneous, but, I believe, is ultimately harmful."

While it's unlikely that margarine will go extinct—butter substitutes for vegans and those on other restrictive diets will always be welcome—its heyday has surely passed. Americans are comfortable with fat again, and have started to prioritize taste and balance over cheap convenience.

And, of course, margarine still has at least one big fan out there. Every time Fabio returns to Italy, he claims to bringing 25 to 30 tubs home to his family. Now there's something I can't believe.