Chew's Hero Bit Into People, And Also Our Culinary Obsessions

Meet Tony Chu. He lives in a world ravaged by avian flu, where all poultry is outlawed, federal food regulatory agencies are our nation's highest policing forces, and dissidents stalk chicken speakeasies for a piece of fried wing or thigh. Working for the Special Crimes Division of the FDA, Chu is a cibopath, able to psychically map the life story of anything simply by taking a taste. A single bite of a tomato will immediately conjure memories of its journey from seed to fruit: its terroir and exposure to pesticides, and even how and when it was plucked from the vine. From hamburgers to human flesh, his superhuman strength works on everything except beets, which he habitually eats to stay not only sated but sane.

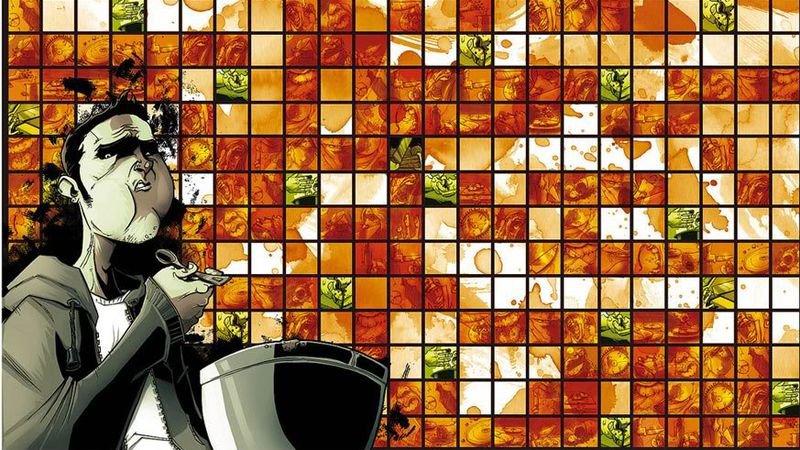

Chu is the lead character in Chew, the award-winning, New York Times-bestselling comic book that satirizes our modern obsession with everything culinary. Since launching the series in the summer of 2009, the writer-artist team of John Layman and Rob Guillory have devised a story filled with as much horror and dark humor as Quentin Tarantino's oeuvre, and just as intricately plotted as Breaking Bad. And like the best shows birthed during the golden age of television, Chew's creators began with an end in mind: The 60th and final issue is scheduled to hit your local comic-book shop on November 23.

Originally conceived as a "weird funny cannibal bird flu book," according to Layman, Chew posited one possible federal response to the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic: an outright poultry prohibition. The first issues of the series read as a simple, albeit gonzo police procedural: Tony Chu and his partners bust a series of black-market chicken vendors while gradually peeling back the layers of a larger conspiracy involving the mysterious death of a U.S. senator, a band of Arctic-bunked Russian scientists, and the Gallsaberry, a tropical fruit that, when cooked, tastes unmistakably like everyone's favorite banned bird.

Despite the fact that ersatz "chickyn" products like Poult-Free fill the marketplace, the absence of the real stuff brings out the crazies. A terrorist organization named E.G.G. takes the president hostage. A doomsday cult worships the Divinity Of The Immaculate OVA. Evildoers fashion weapons out of chocolate, tortillas, peppermints, and clam chowder. And in each and every issue, Chu is there to cibopathically chew his way to justice. For instance, if he wants to know the identity of a murderer, he simply takes a bite out of one of their victims.

It's a precarious premise, with occasional stomach-churning turns and twists, but more often than not, Chew is genuinely funny. Layman and Guillory know when to back away from the pseudo-cannibalism shtick to skewer broader themes like celebrity culture, the drug wars, and genetic engineering.

But Chew is, at its heart, a story about eating, a topic that is often ignored in American comics (compared to the wealth of Japanese food manga). Does Batman pack snacks in his utility belt? Is Aquaman a pescatarian, or is he fin-friendly? There have always been a few comic-book characters who spend their panels noshing—most notably Archie's best pal, Jughead Jones, who turns 75 years old this December. There's also Galactus, the Marvel Universe's villainous "Devourer Of Worlds," and Tenzil Kem, a.k.a. the Matter-Eater Lad, the long-suffering and much-mocked member of DC's Legion Of Super-Heroes, whose sole skill is the capacity to consume any and all forms of matter, including kryptonite and, conceivably, Batman's bright-yellow Underoos. (The poor Lad sprung from the fertile mind of Superman co-creator Jerry Siegel, who winkingly located Tenzil's origins on the planet Bismoll—as in Pepto.)

As Tony Chu's adventures have unraveled over the past 50-plus issues, it's become clear that Chew is essentially an anti-food book with food at its center. Because of his cibopathic powers, Chu is damned to a life of never being able to enjoy a single bite of what he consumes. He is a man, according to the debut issue, who "is almost always hungry, and almost never eats"—because who would want to subsist on beets alone? He must regularly eat outrageously odious things in order to save the day: dead animals, the flesh of loved ones, and all manner of toxic trash. In a way, Chu's diet mimics the real-world culinary cravings for the bizarre, for bites and sips from parts unknown. And it is the bane of his existence.

In the Chew universe, food is not just sustenance for survival. Eating is fun only for the clandestine chicken consumers. Supper is savored only by the wealthy few, such as the Bon Vivant Diner's Club, a group who gathers to dine on rare and otherwise extinct animals (a saber-toothed tiger, a triceratops). In this bizarro world, rather, food is a curse.

In Chew, most everyone—not just Tony Chu—is a supertaster of one sort or another, each burdened with the alimentary albatross that is their superhuman epicurean ability. There are mnemcibarians (who can craft meals that are literally unforgettable); effervenductors (baristas able to control minds with messages written in foam); and at least one galbatatayatsar (a sculptor of mashed-potato golems). Chu's girlfriend, Amelia Mintz, is a restaurant critic and saboscrivner, with the power to write about food with such rich detail and feeling that her words can actually impart the sensation of taste, forever leaving her readership constantly hungry for more. His twin sister, Toni, is a cibovoyant, able to divine the future of any living being with a single bite, but doomed to know her own fate. And though there are a few powers most of us wouldn't mind having—like the cognominutus, who can decipher any menu in any language, or the hortamagnatroph, who can grow Godzilla-sized produce—most every character is driven mad by their food-derived powers.

And that's what makes Chew infinitely more interesting and important than the zombie-centric fare with which the series is often compared. Going head-to-head with the characters, both living and undead, who populate The Walking Dead—the modern zombie genre's dominant franchise, and the comic industry's biggest success story of the 21st century—Tony Chu's struggles are infinitely more engaging. He is simultaneously a zombie and a survivor, at once beholden to and appalled by his own appetites. For all the Jughead-ian joy that food provides, it can also be disgusting, deadly, derisive, and, at its worst, nonexistent. Chew covers all of these bases. Food corrupts. Food kills. Food brings families together around the holiday table, sure. But it can also divide them among bitter battle lines over how the turkey should be prepared (or, in the Chu family, if an illegally procured bird should be served at all). And yet, we keep on eating. Because we must, of course, but also because sometimes it feels like it's the only thing in the world that matters.

With just two issues remaining before the series' end, Chew, like all good fantasy literature, will pit its protagonist against the very end of the world. While it's not exactly clear what Chew's creators have in store, Tony will no doubt have to reluctantly consume something—and more than likely someone—before the planet is overrun by an alien invasion or some such malevolent force. Chu's final bite will unquestionably be unpleasant, horrific, and quite sad. And Chew's fans will be reminded that there are few superheroes this multidimensional, and fewer literary characters we'd rather never share a meal with.