Deep Cuts: A Beginner's Guide To Cooking Offal

Offal—the organs and other bits of an animal typically discarded by butchers, also known as variety meats or an animal's fifth cut—doesn't always get the love it deserves. Most people know that plenty of immigrants to the U.S. cook with offal, from Chinese chicken feet to German liver dumplings to Mexican tongue tacos to Thai blood soups. Offal even features in a few regional homegrown American food traditions, from mid-Atlantic scrapple to Cajun boudin sausages to Ohio River Valley brain sandwiches to St. Louis snoot sandwiches. And sure, large swaths of the nation have in recent years come to embrace a few types of meat once considered offal, like oxtail, beef cheek, pork skin (also known as rinds), and various types of lard.

But even as the "whole animal" culinary movement has made offal somewhat chic, most Americans aren't cooking it on the regular. Why? Many of us just don't know how.

According to United Nations data, as of 2011, America ranked 135th in the world for offal consumption. In 2016, we exported 150,000 metric tons of cow offal alone abroad rather than eat it ourselves. And the rest, says offal-cooking expert Jennifer McLagan, is often ground into pet food, or just dumped.

It's a damned shame, because eating offal just makes sense. The average livestock animal is, after all, 3-6% blood alone, well over 10% bone and marrow, and a good amount more organ and extremity. Daniel Okrent, the New York Times's first public editor and a member of New York City's Organ Meat Society, an offal-eating group, says the most effective argument he can make to variety-meat skeptics is this: "They taste really good."

Fortunately for those willing to give it a shot, it is getting easier to procure offal from supermarkets or local butchers. Common variety meats, such as liver, tongue, and a few others, show up in some supermarkets, says Derrell Peel, a variety-meat expert from Oklahoma State University. Of course, exactly which cuts are available will vary widely by region. Asian markets often sell frozen or coagulated blood, chicken's or pig's feet, beef tendon and tripe, and other types of offal. And as an added incentive, offal is often much cheaper than traditional or prime cuts.

This does not mean, McLagan cautions, that you can go out, ask for a calf's brains, and get them immediately. You may need to put an order in ahead of time. (You also, it is worth noting, can't get lungs in the US. It has been illegal to sell or use them as or in food since 1971 due to fears that phlegm in the lungs could transmit pulmonary diseases like tuberculosis.) It is also easier than ever to learn how to work with offal, as celebrated chefs like Fergus Henderson and Chris Cosentino have put variety meats on their menus and written cookbooks about them.

Still, diving into offal for the first time is daunting. There are dozens of types of variety meats to choose from, all with their own tastes, textures, and preparatory considerations. Consider what's below a cheat sheet to offal—how each type tastes and feels and any major considerations involved in procuring or preparing them—sorted roughly in order of their accessibility for newbies.

Liver

Liver is so common, especially when ground down and mixed into a mousse or paté, that for many, the term offal hardly applies to it. Liver is also easy to develop a taste for. It has a rich and earthy flavor and is far softer than muscle meat—in part because it lacks the fiber bundles that impart a grain to traditional cuts of an animal. The exact flavor and texture of liver can vary by animal; some are a bit grainier or smoother, some a little heavier or lighter. Just don't eat dog, polar bear, or seal livers because they contain toxically high levels of certain vitamins—not that you'd try.

Heart

This is a slightly more challenging bit of offal, given its more recognizable shape when purchased whole, and the fact that it is harder to find in your average store than liver. Yet it will likely be an easier sell than liver for many in terms of taste and texture. At the end of the day, the heart is just a muscle—albeit a very tough, dense, and chewy one given how hard it works. So it tastes, and can be prepared, like any other type of meat. You can even grind it up raw and serve it as a tartare, although it might be better to start by cubing, marinating, and threading the pieces on skewers and grilling them to make anticuchos, a quintessential Peruvian street food. Most butchers will offer to clean it of any clinging external fats and chop it up for you if the shape of a heart bothers you, making it look like any store-bought chopped red meat.

Gizzards

These specialized stomachs most often found in birds grind food up rather than slosh it around in acid, so they are tight and springy muscles. That puts them in the same general taste category as hearts. Their tough texture and size can be just a little less familiar to folks, though. Still, they're easy to work with: just grill 'em, fry 'em, pickle 'em, or put 'em in a stew, stuffing, or gravy.

Tongue

Another hard-working muscle, tongue tastes like other traditional cuts of meat, though at times with a hint of sweetness at the swallow thanks to the amount of gelatin in this organ. But tongues are even more recognizably akin to our own visible body parts than hearts and thus tough for some folks to wrap their heads around—especially since it's harder to procure them in chopped form. The thick skin surrounding the tough and springy meat of a tongue peels right off, and the meat becomes tender when slow cooked. From there, it's a simple matter of ripping up hunks of meat and throwing them into a taco or onto a sandwich. It is easy enough to find sliced in specialty delis (especially traditionally Jewish-American joints) or pickled, jellied, or corned, if you really don't want to deal with a whole tongue and its thick skin.

Kidneys

Given their role as blood filters that produce urine as a byproduct, kidneys can at times carry "a fine tang of faintly scented urine," as James Joyce put it in Ulysses. They also have a less traditionally meaty, more rubbery texture. And they are often surrounded by a particularly tough fat, called suet, that may be unfamiliar to many home chefs. But fresh and high-quality kidneys do not have as much of an odor or tang about them, and ample rinsing and salt water soaking can remove the rest of it. A butcher can clean the fat off from kidneys as well.

Then it's a simple matter of preparing kidneys like you would most other types of meat—although their taste varies by animal, they too have the earthy, gamey flavor of many other organs—and enjoying their subtle springiness. But one common and beloved modern preparation that makes for a good first taste would be deviled kidneys: Slice them in half, remove any fat, dust them with pepper-spiked flour, then fry them up in a gob of spiced, melted butter for a couple minutes and eat them on toast.

Marrow

There are two distinct types of marrow: bone and spinal. The latter is rubbery and thick, and you probably won't find much of it. Bone marrow, on the other hand, is the gelatinous red-and-yellow material at the center of animal bones—easy to source and simple to cook. Roast it in-bone and it turns into a fatty, buttery mass that's delicious spread on crusty bread or added to gravy as a thickening agent.

Glands

This category is broad. It encompasses the pancreas and thymus glands, but also at times the parotid and other glands, because they are all categorized as "sweetbreads." Though their shapes are diverse, from the round ball of the thymus to the handgun shape of the pancreas, they have a similarly mild-to-neutral flavor and soft texture, and require soaking in order to easily peel away from their exterior membrane. The light flavor and lack of rubbery texture make them palatable—especially when they are battered and fried up, one of the more common sweetbread preparations (though hardly the only one). As Joe Satran of HuffPost once put it: "You like chicken nuggets," with their soft texture and mild flavor? "You'll like sweetbreads."

Intestines

Though they constitute one long (we're talking dozens of feet) digestive tract, intestines vary in width and texture and thus in usage depending on the animal. Most folks probably know that many cultures have long used at least small intestines as casings for sausage. To do so, one must scape away exterior matter and flush them out thoroughly with salty water, removing any digestive matter. Thus cleaned, they become simple vehicles for more powerful flavors, but have a nice elastic snap to them that artificial casings, made most often out of cellulose and collagen, usually lack.

Cleaned small intestines can also be fried up on their own (e.g. as chitterlings), like little rubbery segments. The last section of intestines just before an animal's rectum, often known as bung, can also be blanched and served up in thin slices. Without thorough cleaning, bung slices can hold some manure-like flavor which certain cultures don't mind, but which can be challenging to outsiders. (Worth checking out: A classic This American Life investigation into claims that certain restaurants pass off blanched pig bung as a substitute for rubbery rounds of calamari.)

Heads

It can be hard to get over the idea of working with a whole animal's head because, well, it is definitely a face staring up at you—even skinned and robbed of its eyeballs and ears. But the meat you get off of an animal's cheeks, or from behind its eyes is beyond tender—light and thin and delicious. All you have to do is roast up whatever skull you've got, whole or hacked into bits (or boil it, grill it, etc.), and pick the meat off. Traditionally these meats and other bits like slices of tongue were worked into animal gelatin then cooled and set as "head cheese" or "brawn," a common cold cut in some old-school or specialty delis to this day. And it is easy enough to replicate that process at home if you have the hankering. But in the end, it is just another type of meat to work with. The source is just a visceral shock for some to face head-on.

Tendons

You've probably encountered this collagen-based connective tissue linking muscle to bone when eating traditional meat cuts. In that context, it was probably a tough and chewy fiber, devoid of independent flavor to compensate for its annoying texture. But tendons can be a dish of their own, whether served cold and tough, or slow-heated to break them down into a quivering, gelatinous mass, often added to soups as a thickening agent.

Their neutrality is actually a bonus in many preparations; they soak up flavors like crazy, turning into intensely textured vehicles for spice blends, broths, and other tastes you want to highlight. Toss them into a pho broth to kick up your soup's savory factor by a notch or two. Or if you want to experience tendons exclusively and directly, look into a Sichuan spicy beef tendon recipe: Braise the tendons in water, wine, spice, and soy until they're tender, then cool them to firm them up, and cover them in a tongue-numbing peppercorn dressing.

Tripe

A catch-all name for animal stomachs, which vary wildly in texture depending on the animal, tripe is common in dishes around the world. This may be because, like tendon, cleaned tripe is a little bland on its own but acts as a flavor sponge and welcome texture—a chewy edge to a soup or taco. That thin, rubbery feel is not immediately familiar to many American eaters, though, and can be off-putting at first. Tripe is also tricky to prepare from scratch on your own, as, if not thoroughly cleaned out, it can carry a rancid, sour, and altogether gross taste of digestive material into any dish. Fortunately, most markets or butchers will sell reliably cleaned and flavor-neutral tripe. If you have a good half day to slowly simmer tripe, skim off fat, and then boil it with a pepper blend and a few other spices, consider starting out with the classic Mexican tripe soup, menudo.

Feet

This is a pretty broad term given how diverse the characteristics of varied animals' feet can be. A chicken foot is all tendon and skin, while a pig's foot (or trotter) will have a little more meat and fat on it, for instance. However most animals' feet are, in some way, rich in collagen—which is why they're boiled down to make things like gelatin. You can make good use of that collagen to flavor and thicken a stew by throwing in some feet—and bring the flavor of that stew back into the trotters in question. Or you can boil them down to softness and then fry them up, smoke them, grill them, pickle them—anything you want to loosen up those tendons just as much as you'd like and impact some flavor. Be forewarned, this can be a time-consuming process.

Ears

Ears are all crunchy cartilage. You could boil them down (like other collagen-dense cuts) into a gelatinous mass that acts as a thickener and flavor carrier. But the joy of ears for most fans is the crunch lurking beneath gooey skin, when they're braised and fried. Satran calls them "meat potato chips." Ears can also be tricky to prepare, though. Pig's ears, some of the most commonly consumed, are studded with hair and slicked with wax that all needs to be sloughed off; the de-haired and -waxed ear then needs a thorough washing and blanching before you fry it up, or take any other approach to it. And if you're not a fan of a cartilage crunch, that may not be worth it.

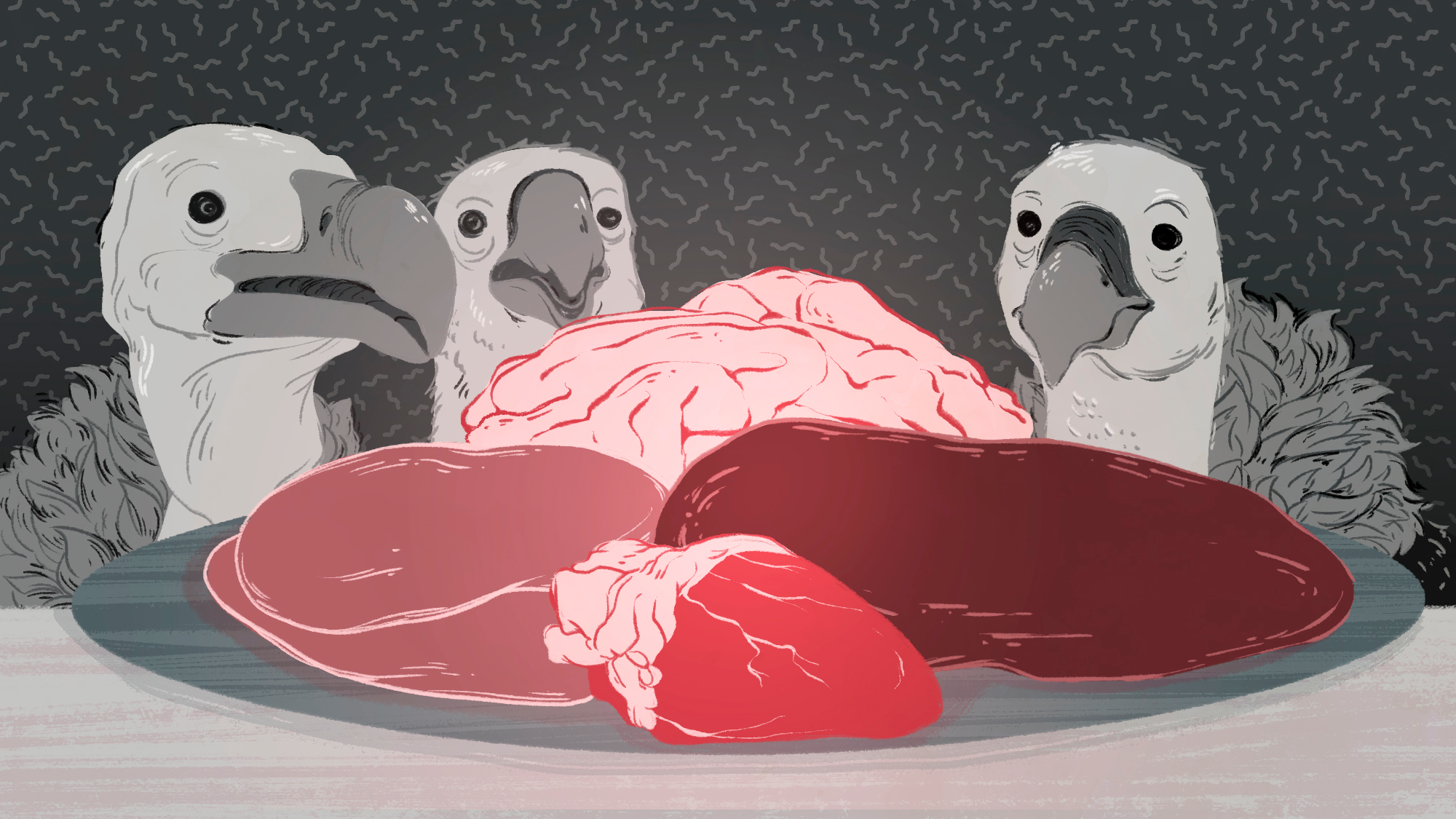

Brains

Visually arresting, a full set of brains conjures up all sorts of biology textbook imagery that can get in the way of viewing this organ as a culinary ingredient. But if you can get over the "ick" factor of eating the center of a being's consciousness, brains are some of the most unique offal available. Delicately soft and creamy, fatty as all get out, "in most preparations, they taste like butter, parsley, and capers," Okrent explains. And they're not all that hard to prepare. Fresh brains just need a good soak to remove excess blood and to loosen up a thin outer layer of membrane that needs peeling off. From there, you can do just about anything with them—sear them so that they're crisp on the outside and custardy on the inside and eat them whole, mush them into a curry (as is fairly common in parts of South Asia), or even make them into a lush paste. Thanks to concerns about mad cow disease, and the fact that brains are nervous tissue, Peel notes that there are restrictions on the sale and use of the brains of cattle that are over 30 days old. And some butchers may be a bit squeamish about them. But in theory, all other brains are very much on the US menu.

Blood

This is perhaps one of the most taboo foods for many Americans, thanks to all of our potential hang-ups about blood (e.g. hemophobia) stacking up on top of our aversions to offal. On its own, it also has a particularly challenging taste—harshly metallic, like sucking on a penny. And if not used fresh or properly preserved, it spoils quickly. Yet blood is a particularly versatile ingredient, used in just about any dish you can think of, from well-known sausage making traditions to perhaps lesser-known pastry making traditions. It adds a rich earthiness to everything it touches, and its metallic flavor is easy to cancel out with just about any other strong flavor. It's even a great low-cholesterol replacement for eggs in many recipes. And so long as your blood is fresh, or well preserved or coagulated, it's pretty plug-and-play. You can even drink super fresh blood, at the site of a slaughter, straight—although few will do so if it's not part of their cultural tradition.

Spleen

Essentially a blood-holding pen and cleaning system, the spleen is a tiny organ that usually finds its way into sausages or other mixtures of meat and offal bits, where its flavor is overpowered by other ingredients. Only a few dishes, like the Sicilian spleen sandwich, really highlight it. The texture is not unlike liver. But if you have trouble with the metallic zing of blood and the softness of many forms of offal, then this is going to be a double trouble organ for you. It's also got a membrane over it that can be a bit of a pain to remove at home. Add to that the paucity of spleen recipes versus other offal, outside of those that use it as filler, and the spleen has to sit low on the list of approachable offal.

Eyes

The only form of offal on the list that this author has not eaten (albeit by chance rather than personal aversion), eyes can be another challenging item for many people to confront, given how alien they are when compared to other organs—squishy and ovular—and how much they remind us of, well, the very lenses we literally view them through. Largely a mix of collagen and water, they are often described as tough and chewy, with little independent flavor. If you're already getting a whole animal's head, it's fairly easy to get eyes—and you might as well try them once you have them. But as with spleen, there aren't many stellar recipes to try; one of the most accessible uses of eyeballs is as a taco filling. It's very little for which to overcome a lot of potential visceral personal aversions.

Testicles

A surprisingly common item in certain parts of America with strong ranching traditions, known euphemistically as Rocky Mountain oysters, "testicles are super delicious," says McLagan. "But they take a bit of work," and if you didn't grow up with them around as a regular part of your culinary environment, "have an ouch factor for some people." Delicate white orbs, testicles are creamy, with a mild flavor but a thick texture that just begs to be covered in a fried out layer. And they're simple to roast or fry or even pickle. However, they require some meticulous peeling as prep work, and handling what is so clearly a ball, especially if it comes encased in a scrotum, is cringe-inducing for some.

This is hardly a comprehensive list of offal. Name an anatomical feature of almost any animal, and there's a good chance humans have figured out some way to prepare and eat it. Penis and uterus, fetuses and unhatched eggs, camel's humps and cock's combs, there are at least a few recipes built around all of them. But the emphasis is on few.