This Is The Jewish Cookbook And You Won't Need Any Other

When I was a kid, Rosh Hashanah meant big family dinners at my grandparents' house, or my aunt's house, or our house, where we'd eat our ancestral soul food: brisket and chopped liver and tzimmes and matzo ball soup, while someone reminisced about Great-Grandma Dora's gefilte fish and wondered if she would ever let any of us have the recipe.

Over the years, the group around the table dwindled. The older folks died, and the younger ones moved away. Grandma Dora did release her fish recipe just a few months before she passed away, but my mom stopped making it because it wasn't worth the labor to feed so few people. And then this year, there were finally only two of us left—my mom and me.

Let me make a confession: Aside from the matzo ball soup, I never really liked any of the food. For a while I thought this made me a bad Jew. More likely, it marks me as a product of the time and place where I grew up: America in the '80s and '90s, land of hot dogs and ice cream and the occasional abomination like skim milk and low-cholesterol fake eggs.

Leah Koenig's magisterial new cookbook, The Jewish Cookbook, is a reminder that all Jews are products of their times and places. There's a reason why, when it first crossed my desk, I didn't recognize most of the dishes. This book is the clearest reminder I have ever seen that Jews come from everywhere—and I do mean everywhere. Koenig has included recipes from Yemen and Uganda and India and Uzbekistan and Tunisia, as well as Spain and Italy and the Middle East and, of course, Eastern and Central Europe, more than 400 recipes in all.

There's a friendly and informative headnote for every recipe that explains where the dish came from, when it's traditionally eaten, and suggestions to make the experience of eating it even more delightful (put sour cream on this one, take that one to a picnic, and this one is what you need on a cold winter's night). Nothing is meant to be too complicated, even the sauerbraten recipe that takes five days. If you want complicated, though, Koenig invited mavens like Michael Solomonov and Yotam Ottolenghi to provide their own chef-y twists on classic dishes. There's also an introduction from Julia Turshen, author of Feed the Resistance, that contains a wonderful story about her grandmother and the philosophy of Jewish food.

My mom and I decided that instead of trying to recreate our lost family dinners, we would cobble together a dinner out of things we'd never tried before. So we flipped through the cookbook and decided we would make chraime, poached salmon fillets in a spicy tomato sauce originally from North Africa. As a side, we chose cheese latkes, sweet pancakes that date back to medieval Italy. Chraime is traditionally eaten at Passover and cheese latkes (or kaese latkes) at Hanukkah, but a festival is a festival.

Before that, though, I started experimenting with recipes that looked interesting to me. I started with Yeasted Pumpkin Bread (recipe below), which I call Pumpkin Spice Challah because, yes, I am a product of my time and place. Koenig writes that in the 16th century, Jewish traders were instrumental in spreading pumpkin, then an exciting New World delicacy, around the Mediterranean; Spanish Jews called it pan de calabaza.

I followed the recipe as written, and the loaf baked up a lovely orange. It was sweet, like regular challah, with traces of cinnamon, ginger, and cardamom. I brought some to a dinner party; the hosts warmed it on the grill and then we ate it slathered with salted butter and were very happy. A few days later, we discovered that the leftovers made wonderful French toast.

It's always a nice surprise when a recipe in a cookbook works the way it's supposed to. A few days later, I made chicken shawarma. Koenig writes that it's impossible to make authentic shawarma without a spit, but her marinated and roasted adaptation, crisped up in a frying pan, made an excellent substitution. I made pita to go with it—there were actual pockets, much to my surprise—and a pungent tomato and cucumber salad, and a garlicky tahini sauce. As long as the leftovers lasted, I felt puffed up with pride and even tweeted about it, although to be honest, there was nothing unusually complicated about any of the preparations.

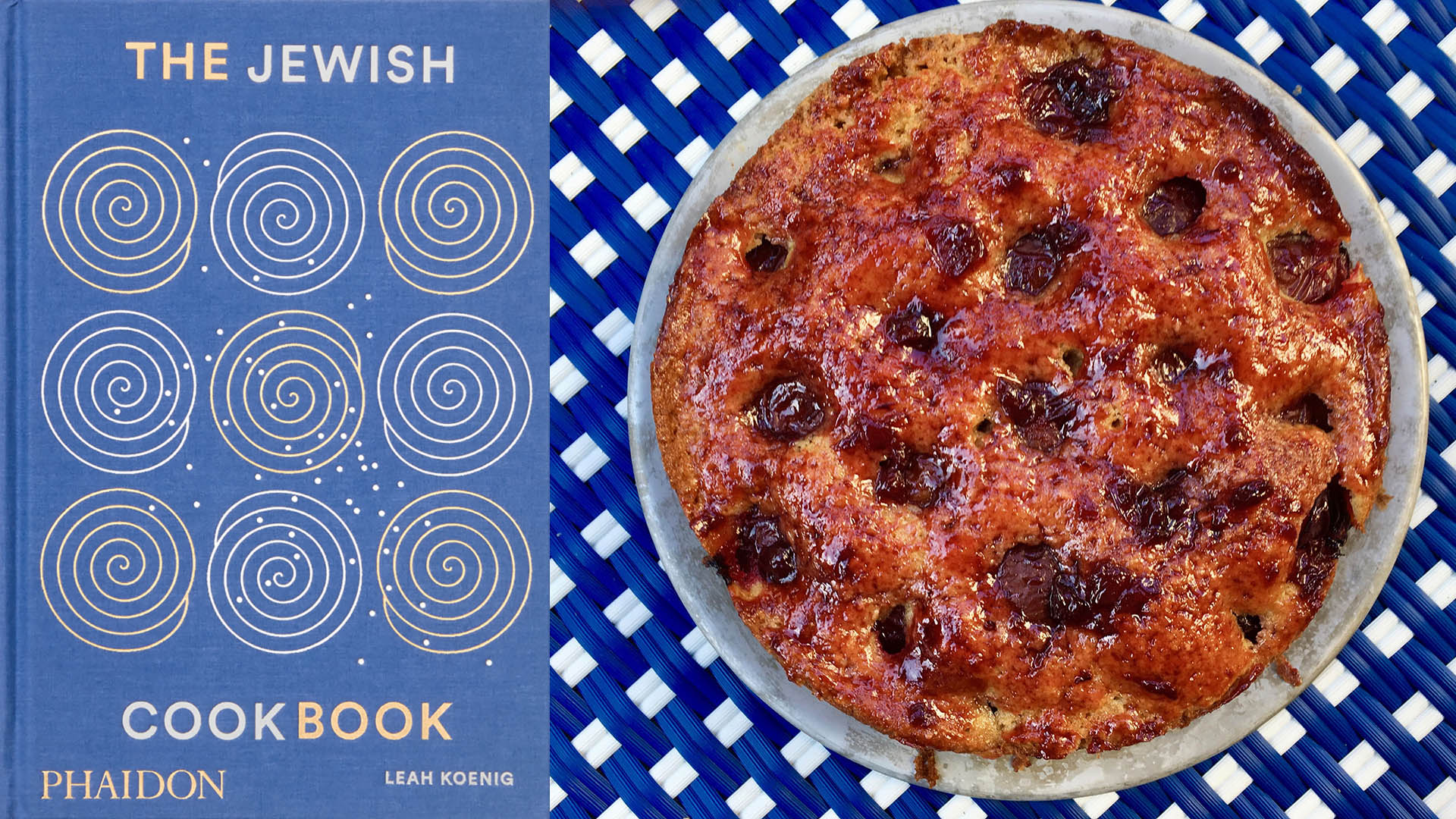

A few days later, some of my friends were gathering to sit around and eat cheese and drink wine and curse men, so I brought a Hungarian plum cake that baked up with a delicate crumb, like a coffee cake, and tasted like it had a much more complex array of spices than plain old cinnamon. In the headnote, Koenig promised that a glaze of apricot or cherry preserves brushed across the top would make it truly special; I went with cherry, and everyone stopped cursing for a minute to agree that she was right.

By the time Rosh Hashanah rolled around, I fully trusted the cookbook. I made a regular challah the day before and brought it over to my mom's house. Then I made the chraime and she made the latkes. We were pretty sure the latkes would taste good, because how could you go wrong with sweet cheese? The chraime, however, was outside our frame of culinary reference. But the smell of sautéing onions and garlic is universal, and it happens to be one of our favorites. While we cooked, we retold family stories.

It took longer to fry the latkes than we'd anticipated. But finally we got to the table and lit the candles. We'd sneaked bits of latke from the pan, so we knew how they tasted (sweet, like cheese blitzes, with a nice assist from a sprinkle of cinnamon sugar, also recommended in the headnote). But then the chraime. We each took a bite.

Neither of us said anything for a minute. Later we would wonder what family members who were no longer with us would think. We weren't sure; some of them had had rather unpredictable tastes. But we knew that we liked it. And that was what mattered now. We ate that old food because it was our family tradition, but it didn't seem right to continue without them. So now we'll eat traditional food from other Jewish families.

Almost as soon as we finished the dishes, we started thinking about what we would make for Yom Kippur.

Yeasted Pumpkin Bread

Preparation time: 25 minutes, plus risingCooking time: 35 minutesMakes 2 loaves

Sephardi Jews traditionally eat foods made with pumpkin and squash on Rosh Hashanah, when they hold symbolic significance. Jewish traders also played a major role in spreading the New World gourd across the Mediterranean during the time of Columbus, and Sephardi cuisine continues to utilize pumpkin in many baked goods, jams, and other dishes today. This tender, gently spiced bread, called pan de calabaza, can be shaped in a spiral for Rosh Hashanah, baked in a loaf pan, or formed into rolls. But this recipe's sunset-colored challah-style braid (plait) is particularly beautiful. Serve it on an autumnal Shabbat or at any fall meal. The leftovers make outstanding Challah French Toast.

- 1 packet (¼ oz/7g) active dry yeast (2¼ teaspoons)

- ½ cup (100 g) plus 1 teaspoon sugar

- 1 cup (240 ml/8 fl oz) warm water (110°F/43°C)

- 4½–5 cups (630–700 g) all-purpose (plain) flour, plus more for kneading

- ¾ teaspoon ground cinnamon

- ½ teaspoon ground cardamom

- ½ teaspoon ground ginger

- 2 teaspoons kosher salt

- ½ cup (130 g) canned unsweetened pumpkin purée

- ¼ cup (60 ml/2 fl oz) vegetable oil, plus more for greasing the bowl

- 2 eggs

In a very large bowl, stir together the yeast, 1 teaspoon of the sugar, and the warm water. Let sit until foaming, 5–10 minutes.

Meanwhile, in a separate large bowl, whisk together 4½ cups (630 g) flour, the remaining ½ cup (100 g) sugar, the cinnamon, cardamom, ginger, and salt.

Add the pumpkin purée, oil, and 1 of the eggs to the yeast mixture and whisk to combine. Add the flour mixture and stir until a shaggy dough begins to form. Turn the dough out onto a lightly floured surface and knead well, adding up to ½ cup (70 g) more flour, a little at a time, as necessary until a supple, elastic dough forms, about 10 minutes. (The kneading can also be done in a stand mixer with a dough hook, 5–7 minutes.) Grease a large bowl with about 1 teaspoon of oil, add the dough, and turn to coat. Cover with plastic wrap (cling film) or a clean tea towel and let sit in a warm place until doubled in size, about 2 hours.

Line a large baking sheet with parchment paper. Gently deflate the dough with the heel of your hand and divide in half. Divide each dough half into thirds and roll each third into a long rope. Pinch the top of 3 ropes together and braid (plait), pinching at the bottom to seal. Place the braided loaf on the prepared baking sheet. Repeat the process with the remaining 3 ropes.

Preheat the oven to 375°F (190°C/Gas Mark 5).

Meanwhile, whisk the remaining egg in a small bowl and brush the loaves with a coat of egg wash. (Set the remaining egg wash aside in the fridge.) Cover the loaves loosely with lightly greased parchment paper and let rise for another 30 minutes.

Uncover the loaves and brush with a second coat of egg wash. Bake until deep golden brown and cooked through, or until an instant-read thermometer inserted in the center of the loaf registers 195°F (90°C), 30–35 minutes. Transfer the loaves to a wire rack to cool for 15 minutes before slicing. Revive leftovers by reheating them briefly in an oven or toaster (mini) oven.

Reprinted with permission from The Jewish Cookbook by Leah Koenig (Phaidon)