Camel Milk Is The Thinking Man's Dairy

Camel milk is healthy and climate-friendly. So what's stopping it from taking over the latte market?

Whether you're cutting out dairy for health reasons, climate reasons, or taste preferences, there are plenty of alternatives to cow's milk on today's market. But a recent CNN article sheds light on an option that may be less familiar among western consumers: camel milk.

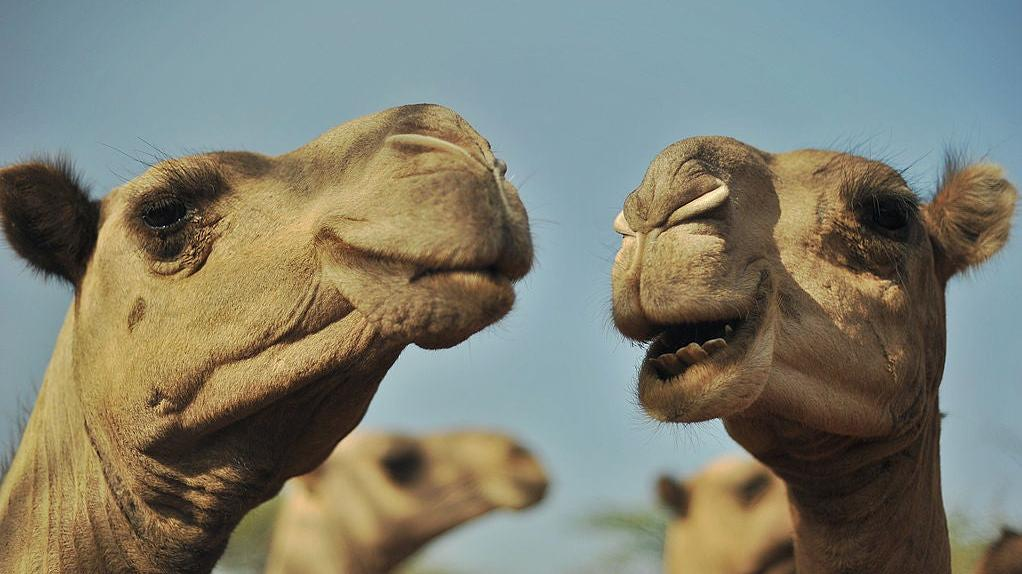

CNN reports that camel milk is consumed across much of the Middle East, Asia, and Australia, as well as within "rural groups" in East Africa. But global interest is apparently growing, with some dubbing camel milk "white gold." CNN even cites one restaurant in central Nairobi offering "camel-ccinos" and "camelattes."

What's so good about white gold? First, camels are a relatively climate-friendly protein and dairy alternative. CNN writes that, unlike herds of cows and sheep, camels can go 100 miles without water and can maintain their cool in incredibly high temperatures. Camel milk is also popular among health-conscious consumers. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization says the milk has triple the amount of vitamin C compared to cow's milk; it's also been shown to reduce cholesterol and improve digestion.

So, why isn't the whole world slurping down that sweet camel nectar? To find out, CNN spoke with David Hewett, a ranch manager for the Mpala Research Center located on the Laikipia Plateau in north central Kenya. "Camel milk on the international market is incredibly lucrative," Hewett told CNN. "Half a liter of finished milk goes for $10 to $20." Compare that with cow's milk, which sells for around 50 cents per half liter in the U.S., and you've got yourself one pricey latte.

Camel milk also lacks what CNN calls an "organized and widespread route to market." It's more commonly found in informal East African markets, especially since most camel ranchers lack access to refrigerated transport, as well as the resources to comply with international disease management standards. Ranching communities would need both of those things to produce a larger-scale product considered suitable for global consumption. Until then, we'll just have to make do with oats.